Martyn James Colebrook

One of the overt criticisms directed towards popular fiction is its requirement for a formulaic structure of characters, plot and narrative, which risks perpetuating the stereotype that all such fiction is repetitious, mass-produced and lacking in depth and originality. Lynnette Hunter surveys different arguments concerning the many definitions for “literature” and identifies one characteristic which is particularly pertinent to contemporary fiction: ‘it uses language in a way that is different from the familiar; hence “popular” writing is not literature because it plays towards convention often because the writer needs to make money’ (Hunter 2001: 13). Additionally, this criticism overlooks the potential for different forms of subversion, parody and carnival which contravene the conventions of genre fiction; language, particularly the use of the vernacular, is one such method for introducing instability. The importance of the vernacular can be seen in such notorious novels as James Kelman’s How Late It Was, How Late (1994), Irvine Welsh’s Marabou Stork Nightmares (1995) and Niall Griffiths’ Grits (2000), where the narrative is filled with colloquialisms and obscenities that are used to attack dominant power structures.

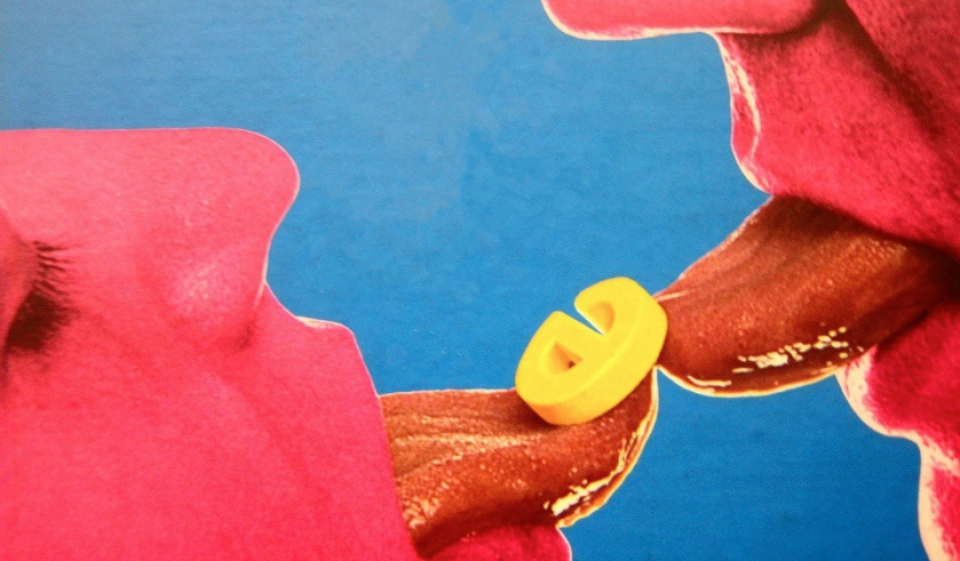

Contemporary transgressive novels [Images used under fair dealings provisions]

The appropriation of language in these novels is thus important in terms of identity formation. There is an argument throughout for the use of language as one element of the oppositional and transgressive force:

A theory of transgression . . . draws attention to popular culture’s role in struggles over meaning. It argues that the popular text is successful because it operates at the borders of what is socially acceptable; and, in order to provoke a widespread interest, the text must, at some level, breach the bounds of that acceptability. It must, in other words, challenge social standards and norms (McCracken 1998: 158).

Many novelists, such as Jonny Glynn, Mark Manning and Bill Drummond and Iain Banks, employ the generic modes of popular fiction and techniques associated with literary fiction throughout their work to enter into a dialogue with contemporary culture as a whole, by exploring how its fringes can be connected to its centres. We can review the corpus of many contemporary transgressive novelists in light of their continued engagements with transgression and genre. As Chris Jenks defines it, transgressive behaviour:

does not deny limits or boundaries, rather it exceeds them and thus completes them. Every rule, limit, boundary or edge carries with it its own fracture, penetration or impulse to disobey. The transgression is a component of the rule (Jenks 2003: 7).

Thus, breaking the rule actually forms a vital and necessary part of the game of fiction because the boundary is then acknowledged. The ‘boundaries’ and ‘limits’ also connote ideas of rigidness and fixed positions, separate areas which are disconnected, thus the repeated undermining of these constraints through the respective portrayals of persona and mental processes contribute in different ways from each other but strongly as a collective to both texts.

Contemporary transgressive novels continue to engage with a tradition of transgression and genre [Image by Ricardo Bandiera under a CC-BY-NC license]

Linking twentieth-century fiction with literature of the twenty-first century, Anthony Burgess’ portrayal of Alex and his Droogs in A Clockwork Orange received a reception as hostile as that levelled against many of the ‘video nasties’ banned in the 1980s for violent and explicit content. Burgess’ reflections on the novel that made him famous tread similar territory to those of contemporary transgressors’ own writing practices:

We all suffer from the popular desire to make the known notorious. The book I am best known for, or only known for, is a novel I am prepared to repudiate: written a quarter of a century ago, a jeu d’esprit knocked off for money in three weeks, it became known as the raw material for a film which seemed to glorify sex and violence. The film made it easy for readers of the book to misunderstand what it was about, and the misunderstanding will pursue me till I die. I should not have written the book because of this danger of misinterpretation, and the same may be said of Lawrence and Lady Chatterley’s Lover (Burgess 1985 [1986]: 205).

The misunderstanding, the elements of ‘jeu d’espirit’ and accusations of glorifying violence are reflected in contemporary transgressive writing and the manner in which many of the novelists previously referenced have been received. The conclusion to Marabou Stork Nightmares where a rape survivor forces one of her attackers to eat his own penis, the violent conclusion of You’ll Have Had Your Hole and the staging of Davie Mitchell’s death in Trainspotting are three such instances.

The renaissance in contemporary Scottish Gothic has sparked the style of fiction which trespasses on the darker sides of the human condition. The most potent figure of the Scottish Gothic is the double, or doppelganger, which Karl Miller claims 'stands at the start of that cultivation of uncertainty by which the literature of the modern world has come to be distinguished' (Miller 1985 [1987]: vi). The manipulation of the double also allows for the gleeful renditions of violence, psychosis and outlandish behaviour that are a mainstay of novels such as Duncan McLean’s Bunker Man, James Robertson’s The Fanatic, Ewan Morrison’s The Last Book You Read and Toni Davidson's Scar Culture. In terms of its impact, then, the literary revival of the 1970s succeeded. Wallace notes, ‘in the compellingly imaginative depiction of Scotland as the one country best designed to drive anyone with the faintest glimmer of imagination quietly insane’ (Wallace 1993b: 218).

Are novels like Irvine Welsh's Ecstasy misconstrued in their exploration of the darker sides of the human condition? [Image by Jayeon Kim under a CC-BY-NC license]

Taking the trope of the ‘insane’ or the ‘damaged mind’, a recurrent feature in Scottish contemporary literature, this damage, whether it be through alcoholism – the subject of Ron Butlin’s The Sound of My Voice (1987) – or the inability to discern between fantasy and reality as in Alasdair Gray’s 1982 Janine (1984), is reflected in the fractured or debased narratives through which the ‘voice’ and ‘narrative’ are articulated. Iain Banks’ Complicity, where the murder scenes are narrated through the deployment of the second person narrator, ‘you’, is one such instance. Gavin Wallace claims that:

[t]here is a new cultural identity celebrated in recent Scottish fiction, but an identity whose instability and claustrophobic intimacy with psychological maiming writers inevitably deplore, yet appear incapable of forsaking (Wallace 1993b: 218).

The cultural identity that is identified seems to be riddled with ambiguous or contrary values. That it is celebrated does not mean that the writings are positive, but that they are revelling in their own fascination with the carnivalesque or the transgressive. This is suggested by the juxtaposition of the ‘deplorable’ identity with the ‘incapability of forsaking’ it – asserting that the persistent presentation of this identity type in Scottish Literature has become an intrinsic part of the nation’s culture, despite the writers’ and critics’ dislike of its presence. There is a sense of frustration and despair here, that to write about such individuals and their ‘instability’ and ‘psychological maiming’ has become an expectation rather than an opportunity for exploration. The despair is particularly evident given the argument remains that:

such motifs have become entrenched as readily identifiable and assimilable literary tropes which, despite their continued creative appeal, may have not only outlived their function, but also become the internalised submission to a condition in which the Scottish imagination will eventually colonise itself (Wallace 1993b: 220).

Arguably the trope of psychological maiming has become too familiar and is in danger of being exhausted – there is a cause for concern that its repeated use will cause the genre to impose limitations of creativity on the authors using it. The genre of the Gothic and the more regionally specific “Scottish Gothic” as a mode for exploring mental illness is rich in its depiction of, and engagement with, the process of Othering and the image of the Double – the fearful figure who becomes the focal point for society’s concerns. By using the Gothic genre, contemporary novelists Patrick McCabe, Iain Banks, Ali Smith and Irvine Welsh, are thus able to provide an intertextual appreciation and understanding of texts which ‘recognizes the play of surface effects as they locate themselves on the unstable boundary between humour and horror and transgress it in both directions’ (Horner and Zloznik 2005: 165). This utilises a technique that is in keeping with the qualities of transgressive contemporary fiction and its practitioners.

Scottish Gothic: exploring the "insane" or "damaged" mind and its punishable transgressions [Image by Fr Lawrence Lew under a CC-BY-NC-ND license]

Twenty-first-century readings of the transgressive in literature also need to respond to the paradigm of postmodernist experimentalism, as Patricia Waugh argues. Connecting gender, monstrosity and contemporary fiction, Waugh suggests that:

Bodies, monstrous, engineered, fantastic and hybrid, stalk the pages of postmodern fiction . . . In such postmodern fictions, the monstrous body functions as a means to voice and overcome anxieties concerning the construction of femininity as uncontrollability, but also concerning the contingency of materiality as a threat to crystalline perfections of rational theory (Waugh 2005: 80-81).

That Waugh sees these bodies as ‘stalking’ the pages of ‘postmodern fiction’ emphasises their sinister status and the threat they pose to existing cultural constructions of ‘femininity’ and ‘masculinity’. Waugh’s use of the terms ‘engineered, fantastic and hybrid’ is significant given that they relate to the type of fiction written in the different genres that contemporary transgressors such as David Britton, Michael Butterworth and Peter Sotos operate in. Similarly, popular fiction is at once an agency portraying social and cultural anxieties and panics whose construction is, paradoxically, market-driven: a genre of fiction perpetually on the periphery of academic acceptance that revels in its capacity for insurrection and parody. It is most generally a product of and representative of the contemporary cultural climate, and explodes the boundaries between “high” and ‘”low” culture whilst engaging in a continuous dialogue with the established literary canon.

CITATION: Martyn James Colebrook, "Transgression and Contemporary Fiction," Alluvium, Vol. 1, No. 4 (2012): n. pag. Web. 1 September 2012, http://dx.doi.org/10.7766/alluvium.v1.4.02.

[author] [author_image timthumb=’on’]http://www.alluvium-journal.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/Martyn-James-Colebrook-thumbnail.png[/author_image] [author_info]Dr Martyn James Colebrook recently completed his PhD thesis, which focuses on the novels of Iain Banks in relation to British fiction after 1970. He has wider research interests in contemporary American literature, transgression and contemporary culture and apocalypse fictions. [/author_info] [/author]

Works Cited:

Bienstock Anolik, Ruth (ed.), Demons of the Body and Mind: Essays on Disability in Gothic Literature (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland and Company, 2010).

Burgess, Anthony. Flame into Being: The Life and Work of D. H. Lawrence (London: Heinemann, 1986).

Burgess, Anthony. A Clockwork Orange (London: Penguin Classics, 2008).

Butlin, Ron. The Sound of My Voice (London: Serpent’s Tail, 1987).

Davidson, Toni. Scar Culture (Edinburgh: Rebel Inc., 2000).

Gray, Alasdair. 1982 Janine (London: Penguin, 1993).

Griffiths, Niall. Grits (London: Vintage, 2001).

Horner, Avril and Sue Zloznik. Gothic and the Comic Turn (New York: Palgrave. Macmillan, 2005).

Hunter, Lynette. Literary Value/Cultural Power: Verbal Arts in the Twenty-First Century (Manchester University Press, 2001).

Jenks, Chris. Transgression (London: Routledge, 2003).

Kelman, James. How Late It Was, How Late (London: Vintage, 1995)

McCracken, Scott. Pulp: Reading Popular Fiction (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1998).

McLean, Duncan. Bunker Man (London: Vintage, 1996).

Miller, Karl. Doubles: Studies in Literary History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1985).

Morrison, Ewan. The Last Book You Read (Edinburgh: Black and White Publishing, 2005).

Robertson, James. The Fanatic (London: Fourth Estate, 2001).

Wallace, Gavin and Randall Stevenson (eds). (1993) The Scottish Novel Since the Seventies: New Visions, Old Dreams (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1993).

Wallace, Gavin. (1993b) “Voices in Empty Houses: The Novel of Damaged Identity” in Gavin Wallace and Randall Stevenson (eds), The Scottish Novel Since the Seventies: New Visions, Old Dreams (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1993), pp. 217-231.

Waugh, Patricia. "Postmodern Fiction and the Rise of Critical Theory" in Brian W. Shaffer (ed.), A Companion to the British and Irish Novel, 1945-2000 (Oxford: Blackwell, 2005), pp. 65-82.

Welsh, Irvine. Marabou Stork Nightmares (London: Vintage, 1996)

Welsh, Irvine. Trainspotting (London: Vintage, 1994).

Welsh, Irvine. You’ll Have Had Your Hole (London: Methuen Drama, 1998).

Please feel free to comment on this article.

Very interesting article and I found myself re-assessing my own definition of what constitutes literature and the genre novel. I had settled on the posing of the question 'does this novel purport to comment on the human condition?'- rather than simply supplying the familiar shot in the arm available from the genre novel.

Very interesting mention of the Scots Gothic, the 'Double' and the concept of 'Other'. I tend to consider the 'Other' very much when thinking of the development of the Irish contribution to English literature and indeed the shadowy 'Other' always visible in the art and consciousness of modern Ireland.

I had not considered the notion of checking the Scots literature for traces of that Other and comparing it with the underground in Irish fiction. Could be an interesting plough to furrow. Thank you for this article.