Holly Pester

A project for poetry and text-based art has emerged over the past two years that tests the limits of what we broadly term as intermedia. The work is Caroline Bergvall’s combined ‘Middling English’, an exhibition at the John Hasard gallery in Southampton in 2010, and Meddle English, a book of poetry and critical writing published 2011. Both negotiate intermedialities through properties of connectedness and extension and the combined project sites the concept of intermedia as a middling process. This signifies a contemporary definition of merged media, as influenced by theorist Michel Serres, that priviliedges the frictions, topographies and the noise of relationality. This is opposed to the twentieth -century handling of Intermedia, as coined by Fluxus artist Dick Higgins in the 1960s, that favours the overlapped divisions of cross-disciplinarity. This middling process of art and poetry is also what marks Bergvall’s practice as crucial to our current theorisations of art practices of writing, as stated by Bergvall: ‘Material noise in relation to verbal articulacy has defined my modes of thinking about writing at its junctures or sutures with media and non-textual environments’ (Bergvall, 2009: 21).

‘Middling English’ was an exhibition of multi-media writings ‘about’ the English language. The works used English as a milieu to seed ideas about the practice of languaging. Accenting her bi-lingualism the artist has developed a praxis that investigates fields of forces experienced by speakers on the limits of foreignness and fluency. The exhibition consisted of sound, installation, sculpture, and image-texts and was therefore intermedial in the practical sense of the word. But this notion of crossing media can be developed to consider the operations put into motion by the work by the exhibition’s extensions. Meddle English shares common texts and conceptual threads with the art show, and also inexplicit points of medial betweeness, instigated by the work’s materials and reflexes. The book’s first sequence of poetry, The Shorter Chaucer Tales, experiments in the ‘materials and reflexes’ of Chaucerian English. Suddenly the Middling and Meddle of the two titles extend their connotations and we realise that the medial shifts in Bergvall’s project are more multiplicitous than the mechanics of the gallery space.

Experimenting with Chaucerian English: Caroline Bergvall’s Middling / Meddle English reworks The Canterbury Tales [Image by Jim Forest under a CC-BY-NC-ND license]

In a paper on Milieux Steven Connor locates a ‘central ambivalence’ in the writing of Michel Serres, and his mediations on crossings and the midst. The oscillation is between two kinds of middle, one being an imaginary, abstract place that is immaterial and does not form part of the thing. The other is more of an action, ‘a middling thing’. He says:

There are two kinds of middle, static and dynamic. There is the abstract middle, or centre, part of a structure which is equidistant from all bounding edges. Then there is the more dynamic kind of middling or mediation, which consists in a movement towards a middle, which never comes to reside there (Connor, n. pag.).

We are reminded that the Latin idiom, in medias res, ‘in the middle of things’, or ‘in the thick of it’, is accusative, signalling a motion towards, therefore better translated as ‘into the middle of things’. This ‘mobile mediation’, continual process of going into the middle, brings to light much of the activities in Bergvall’s ‘Middling English’ exhibition. It is a mixed-media show but the thread never settles in any object. Its textual extensions write themselves through the gallery space, revealing media as such to be unstable and shifting. The show is itself a process of going into media, pushing form through structures that reveal the entropic nature of language spilling away from form. Bergvall uses media to get into the midst of speech, putting material and immaterial elements into mobile mediation.

The exhibition is cohered by a central sculptural structure; lengths of wire weighted by bright orange dumbbells, described in the catalogue as ‘[a] site specific mobile structure flowing along the dynamic lines of the gallery space itself.’ The structure is both navigating and obstacle, orientating and disorientating. It is somehow linguistic, with the lengths halted by weights like punctuation marks. This piece yields significance for the whole project as it illustrates a mobile sense of projective space. It references behind and in front, before and after. It is a topological design concerned with relationality, giving architectural momentum to the gallery visitor going into the gallery space, into media and a sense of language.

Linguistic mobility: Bergvall’s scupltural dumbbell structure and the cover of Meddle English [copyright: www.thewire.co.uk / www.carolinebergvall.com] [Source.] [Source] [Copyright: Caroline Bergvall. Images used under fair dealing provisions]

A key audio piece is, ‘wired madeleine’, a composition made from lines of seminal pop songs. All the songs are listed on the wall and include Kate Bush’s ‘Hounds of Love’, Anita Ward’s ‘Ring my Bell’ and Diana Rosss ‘Upside Down’. Consequently there are lots of ‘baby do this’, ‘baby do that’, imperatives, declarations, confessions, innuendo (‘pull up to the bumper baby’). How do we experience this sound in the ambience of metal wire? In the catalogue’s foregrounding essay, similarly named ‘Middling English’ Bergvall talks about a ‘tissue of lines’ that converge throughout this body of work and cultural experience as such:

There are lines that draw from one node to another, one bell to the next, towards the architectonic structure, spatial resonant membranes of interconnections and tendencies… There are lines of travel, trade routes, blood routes. Intense seasonal species’ traffic, migratory paths … Dissenting lines or lines of flight that sustain or dissolve under lines of fire, buzz lines, rumours. Songlines, memory structure, great pick-up lines (Bergvall, 2011: 5).

This sets up a virtual continuum of experience and memory, as figured by language. The nostalgic pop lyrics direct experience in and out of the room, the wires navigate your body in and out of the space.

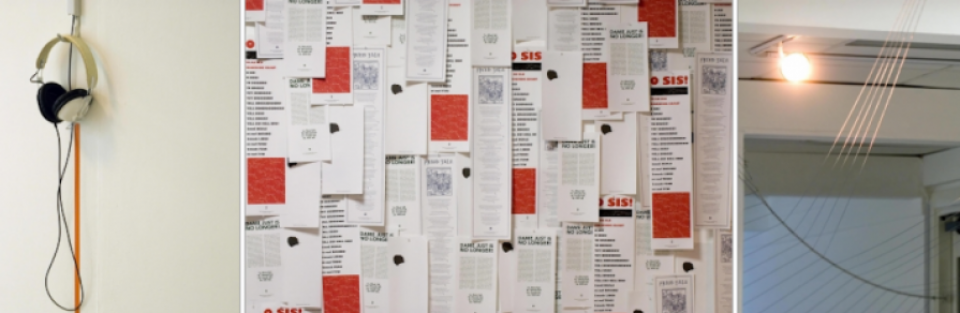

Another key work is the ‘wall of pins’, a wall of broadsides ballads or single-sided sheets of printed paper, emulating the fifteenth and sixteenth century with popular forms of ‘come all ye’ ballads on religion, drinking-songs, legends, and early journalism. Essentially broadsides were the ‘low’ form of information transmission; popular, gossip and hack writing with a sing-song bawdiness we associate with the Canterbury Tales. What is it to step-into this medium in the otherwise very contemporary gallery and articulate the rhetoric, prosody and energetic broadcasting of the broadside?

Low forms of English: Chaucerian vernacular, popular broadside ballads, gossip, hack writing and science fiction [Source] [Copyright: Caroline Bergvall. Image used under fair dealing provisions]

Bergvall’s broadside nod to all perpetual melting pots of ground-level speech-exchange, sites of language deformation and spawning. As in much of Bergvall’s work letters and symbols are spores that germinate and evolve. A broadside called ‘Fried Tale’, is a sequence sourced from various literary texts. It takes from Russell Hoban’s Riddley Walker, Anthony Burgess’ Clockwork Orange, The Matrix, tabloid headlines and ‘The Friar’s’ tale’ from the Tales. It is similarly a tale of bribery and extortion in a pertinent narrative that follows hedge funders gloating over money, all told in a soup of corrupted Chaucerian English:

2 Suits, a mega pair of Smith, Blupils no doubt,

viddying how they trading outa goodness welth stuporifik,

shake hands, hug n abuse ech other on the bak.

It’s a total blowout! We tawking millions a squilyons,

zilyons a nanilyons, bilyons a teramilyons

jus 4 kreaming the topping, o my brother (Bergvall, 2011: 38).

It’s a contemporary scene played as an historical satire, in a muddy mix of old language mediated by new, new language figuring Old English, fictional slang and jargon becoming re-mediated. Again Connor’s reading of Serres is useful here, in which he considers history as a ‘complex overlayering of time’ like baker’s dough: ‘In the folding and refolding dough of history, what matters is not the spreading out of points of time in a temporal continuum, but the contradictions and attenuations that ceaselessly disperse neighbouring points and bring far distant points into proximity with one another’ (Connor, n. pag.).

Bergvall creates a milieu that is also a medium, an environment that is also a channel. The texts behave like spatial relations. In the swerves from each node a subjectivity, a voice or a history is pricked. The broadside is an extract from a longer piece from The Shorter Chaucer Tales sequence. The poems in the sequence adopt much of the language and style of the Canterbury Tales, variously mixed with contemporary narrative, ‘current affairs’ and found-texts. The ‘Host Tale’, the only poem constructed entirely of found-text, is every line from the Tales which refers to food or drink:

And of youre softe breed nat but a shyvere,

And after that a roasted pigges heed

Milk and broun breed,

many a muscle and many an oyster (Bergvall, 2011: 25).

Though procedurally composed we still get a narrative route of feasting, a sense of different stages of gorging, swallowing and digesting substances. It has an atmosphere of drunkenness and consumption. Its title and status as the ‘Host Tale’ is telling in that it provides the food and the codex for the following poems to exist through, creating a milieu of Chaucerian sounds and idiomatic matter to indulge on. Bergvall is feeding on Chaucer and letting it feed the texts that spawn from it. Throughout the ‘Middling English’ exhibition and the Shorter Chaucer Tales there is an accumulation of extensions and substance. The works orientate to create a space. Not a static space but a dynamic topos where agents and things go into media; milieuing, middling and meddling. Space is given linguistic meaning, becoming place. The coded gallery space spills out into the texts and the lineages of English. But the creation of a spatial experience of language is a means to show how forms of English displace and fix its speakers within identities. It’s about what language does to personhood; how it infects and deforms it.

CITATION: Holly Pester, “Intermediality: Middling and Meddle English,” Alluvium, Vol. 1, No. 4 (2012): n. pag. Web. 1 September 2012, http://dx.doi.org/10.7766/alluvium.v1.4.01.

Holly Pester is an AHRC-funded PhD student in the Contemporary Poetic Research Centre at Birkbeck, University of London. Holly teaches English on Birkbeck’s BA programme, and her first collection of poetry, Hoofs, has recently been released with if p then q press.

Holly Pester is an AHRC-funded PhD student in the Contemporary Poetic Research Centre at Birkbeck, University of London. Holly teaches English on Birkbeck’s BA programme, and her first collection of poetry, Hoofs, has recently been released with if p then q press.

Works Cited:

Bergvall, Caroline. Meddle English (San Francisco: Night Boat Books, 2011).

Bergvall, Caroline. ‘Caroline Bergvall Talk’ in Robert Sheppard (ed.), ‘Birkbeck Launch Event 2009: Selected Papers,’ Journal of British and Irish Innovative Poetry (2009): 21-24. http://www.scribd.com/doc/22924473/Journal-of-British-and-Irish-Innovative-Poetry-Birkbeck-Launch-Event-2009-Selected-Papers [accessed 27 August 2012].

Connor, Steven. ‘Michel Serres’s Milieux,’ extended version of a paper given at the ABRALIC (Brazilian Association for Comparative Literature) conference on ‘Mediations,’ Belo Horizonte, July 23-26 2002: http://www.bbk.ac.uk/english/skc/milieux/ [accessed 01/05/2012].

Please feel free to comment on this article.