by Dave Owen

Introduction

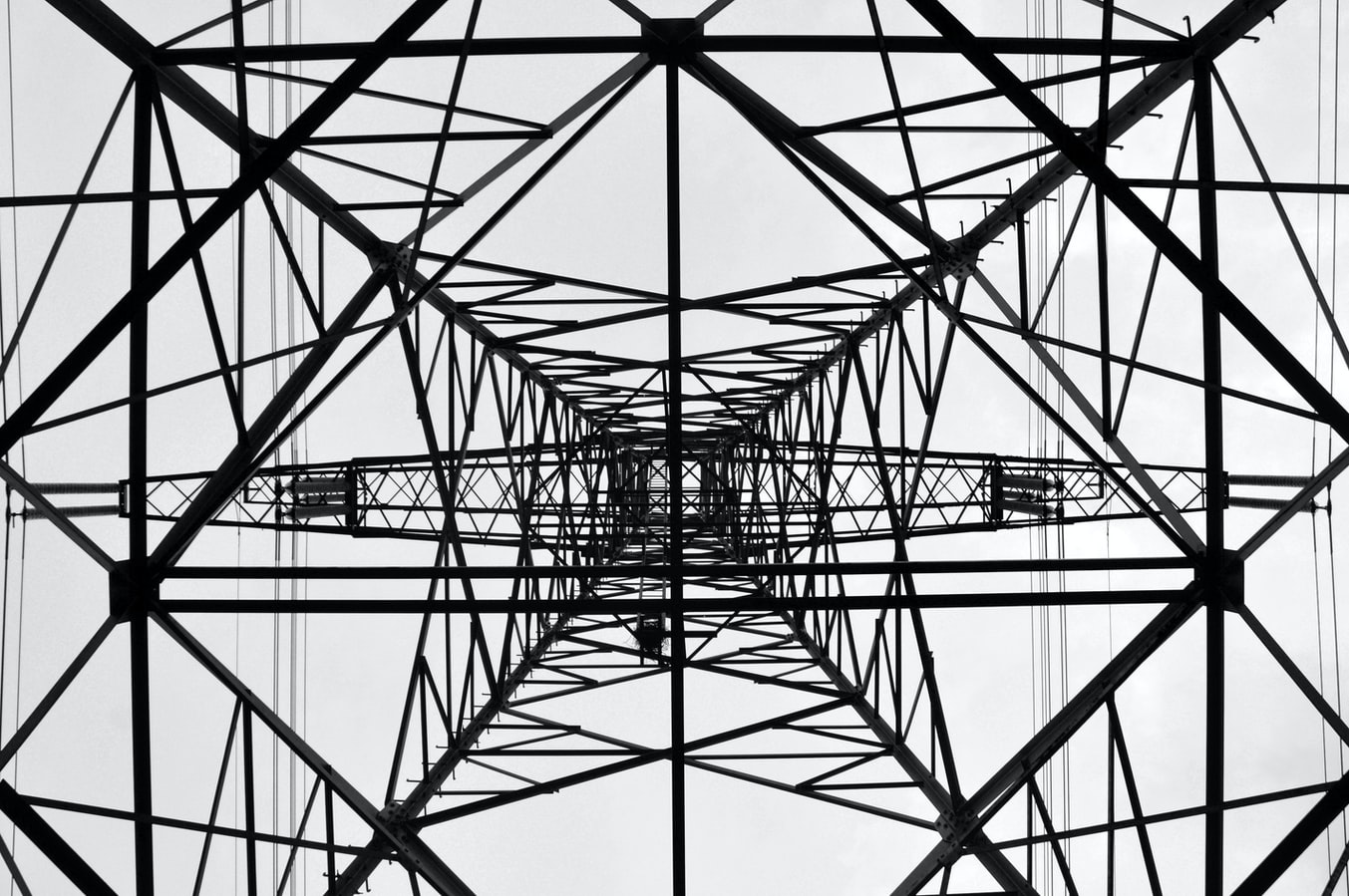

Infrastructures are technologies which facilitate fundamental operations and systems within a society (Cambridge Dictionary n.p.). Infrastructures often appear mundane, with examples including roads, public transport systems and government buildings. However, their pervasiveness, alongside the roles they play in the structuring of everyday existence, make infrastructures political objects. Anand, Gupta, and Appel (2018) describe infrastructures as “social, material, aesthetic, and political formations that are critical both to differentiated experiences of everyday life and to expectations of the future” (3). This understanding informs Infrastructure Studies, a critical field which examines how experience with infrastructure informs the material conditions and political imaginations of citizens.

Adjacent to this growing area of criticism is Weird fiction. The Weird is a genre of speculative fiction, the narratives of which are concerned with ruptures of experience (Fisher, The Weird and The Eerie 22). These ruptures are communicated through the fantastical transformation of the material, whether that be through body horror or characters’ physical surroundings. In this article, I will explore the link between these ruptures of experience and the aesthetics of infrastructure, demonstrating how contemporary Weird fiction conveys the role of the latter in structuring the political experiences of the citizen. I will also examine how Weird texts signal the role of the state in potential, utopian futures. My analysis will focus on novels by Jeff VanderMeer and China Miéville, two of the most prominent contemporary Weird writers. This article is grounded in textual analysis of the novels Authority (2014) and The City and The City (2009), specifically.

Ruptures of Experience

In The City and The City (Miéville) and Authority (VanderMeer), infrastructure plays a crucial role in encounters with the unknown. Writing regarding the fiction of H.P Lovecraft (a seminal figure in the canon of Weird fiction), the cultural theorist Mark Fisher (2016) notes that the genre is concerned with “the difference between the terrestrial-empirical and the outside” (Weird and Eerie 20). Fisher comments that Weird narratives display a confrontation between the perceived rationality of human societies and a monstrous, indescribable “other”. They facilitate an encounter with the “unknown”, resulting in crises of epistemology characterised by “ruptures in the very fabric of experience itself” (22). Kate Marshall (2017) has noted that the contemporary Weird has philosophical concerns grounded in new materialism and object-oriented ontology (633). I posit that in centralising ‘ruptures of experience’ in the material object that is infrastructure, Authority and The City and The City communicate the extent to which it shapes the political imagination of the subject.

In regard to ‘encounters with the unknown’, Authority, the second instalment in the Southern Reach Trilogy, is distinct. In the texts preceding and following Authority, Annihilation and Acceptance (both 2014), the ‘unknown’ appears within the first stages of the narrative. By contrast, this genre device is reserved for the final moments of Authority. Control, the protagonist, comes into contact with the ‘unknown’ when walking the corridors of the state-funded Southern Reach research facility, an example of concrete, modernist infrastructure. Prior to this moment, Control’s experience with Area X (the ‘outside’ force transforming the landscape of the narrative) is mediated through CCTV and third party accounts. However, when searching for a door handle contact with Area X is made clear:

But there were no doors where there had always been doors before. Only wall.

And the wall was soft and breathing under the touch of his hand.

He was screaming. (VanderMeer 290)

In making the wall “soft and breathing”, Area X makes what should be hard, soft and what should be inanimate, animate. Through this inversion, the wall challenges empirical rationality and in turn, the preconceived notions of reality held by Control. Writing regarding the political aesthetics of infrastructure, the academic Brian Larkin (2018) argues that tactile interaction with infrastructure facilitates a “reciprocal exchange between the material and the figural” (177). The writer Elvia Wick has noted that the Weird is distinct from other forms of fiction in its literalising of metaphorical transformations (n.p.). In practise, this means that a breathing wall, in the Weird, would be read as a living creature rather than a mere metaphorical flourish. This literalising deconstructs assumptions that are inherently ideological and is a feature of the genre’s confrontation with “empirical rationality” (Wick n.p.). Read in these terms, the animating of the wall demonstrates a literalising of the figural, through the material (the wall). As such, like the tactile mechanisms of political aesthetics outlined by Larkin, this moment demonstrates a reciprocal relationship between “the material and the figural” (Wick n.p.). By presenting this reciprocity, Authority communicates an understanding of the experiential power of infrastructure.

Similarly, infrastructure crucially facilitates genre elements of the Weird in The City and The City. In Miéville’s novel, the constitutional uncertainty of border policing functions as the fantastical, ‘outside’ force of the Weird. Its narrative is set in Besźel and Ul Qoma, two city-states in conflict. This is complicated by the unusual geographical circumstances of the cities, whereby the streets of each are interwoven with those of the other. If citizens enter the city that is ‘other’ to them, they are violently arrested by Breach, the security body that polices the border. Described as an “alien power”, its humanity is obscured; Breach are “unclear figures” with “faces so motionless”, “grim-featured something” and “dark shapes” (Miéville 285–286). When describing Breach, its location, mechanisms and constitutional authority remain ambiguous. Theodore Martin argues that it is through this ambiguity and constitutional uncertainty, that Breach gains its power: “The uncertainty of Breach’s legal and geographical standing (To whom do they answer? Where are they located?) becomes a way of managing the ‘urban uncertainty’ of the cities. Breach’s constitutive uncertainty is what allows the cities to be certain of their separateness” (113–114). The uncertainty surrounding the legal and geographical position of Breach, combined with its obscured humanity arguably presents Breach in the imagery of the ‘unknown’, ‘outside’ force, characteristic of the Weird fiction narrative.

The power of Breach is demonstrable through its relationship with urban infrastructure. Whereas citizens must take pains to avoid crossing into either city, Breach is able to use mundane urban infrastructure, such as streets, as its design intends. This is demonstrated when Borlú (the protagonist) and Breach collaborate, with Breach transcending the borders of the cities:

He walked me down the middle of the crosshatched road.

My sight seemed to untether… some trickery of dolly and depth of field, so the street lengthened and its focus changed . . .

Sound and smell came in. (Miéville 303)

In this extract, the power that Breach derives from utilising urban infrastructure is revealed through Borlú’s response. When mimicking the actions of Breach (walking down the street), Borlú has a profound sensory development: his sight becomes “untethered”, smell and sound arrive. Alongside these enhanced senses, Borlú’s movement is liberated: moving from Ul Qoman metro to Besz tram with ease, he notes that it is a “strangeness” that “felt good” (Miéville 304). Represented by this liberation of senses and movement, the power of Breach is also shown in the comprehensive utilisation of the cities’ urban infrastructure, a freedom that is not prescribed to their citizens. As such, the power of the outside force in The City and The City is firmly grounded in infrastructure.

By positioning government buildings, roads and public transport systems as the primary spaces by which the outside enters and experience is ‘ruptured’, both novels tie infrastructure to the fundamental devices of the Weird fiction genre. This, in turn, demonstrates the significance placed by the Weird on the radical potential of infrastructure and how it can inform political experience.

Façades, Utopias

Larkin argues that “infrastructures, as technical objects, take on form” (175). This form, as in the arts, can be analysed in order to understand its political aesthetics. When understood as such, infrastructures contribute to citizens’ sense of time, engendering feelings of nostalgia, hope and desire. These emotional responses are ultimately political as infrastructures, being funded or approved by government, “implicate the very definition of community, its possible futures, and its relation to the state” (Larkin 175–176). When examining the form of infrastructure in Authority and The City and The City, it becomes clear that they signify versions of the future defined by collectivism and a greater role of the state. In doing so, both texts provide discourses on futurity and the potential for the state to facilitate a radical, ‘utopian’ society.

In The City and The City, Miéville details how Ul Qoma previously had a socialist political economy. Signifiers of Ul Qoma’s socialism are still present in the physical world of its cityscape. Its brutalism exemplifies this: “The Ul Qoman transit used to be more Brutalist than any – efficient and to a certain taste impressive, but pretty unrelenting in its concrete” (Miéville 200). As an architectural movement, Brutalism has been associated with socialism and broader utopianism.

In post-war Europe, Brutalist architecture was frequently erected in the building of social housing programmes. Continuing his research regarding the relationship between architecture and activism, Oli Mould (2017) outlines how Brutalist architects regularly conceived their projects as facilitating communality between their inhabitants in an attempt to create housing with “utopian” ethics (711, 716). Fredric Jameson (1991) elaborates on this in order to outline the disparate political aims of modernism and postmodernism, comparing the “modern”, concrete architecture of Le Corbusier with the glass “skyscraper” architecture built under postmodern contexts (40–41). Jameson argues that whilst both forms of architecture attempt to be distinct from the surrounding city, these “disjunctions” have different political results (40–41). Modernist architecture “radically separates the new Utopian space of the modern from the degraded and fallen city fabric which it thereby explicitly repudiates”, whilst the postmodern “aspires to being a total space, a complete world . . . it does not wish to be part of the city but rather its equivalent and replacement or substitute” (40–41). The concrete transit system of Ul Qoma exists underneath the “mirrored steel” and “doorways of glass blocks” of its financial district, which is portrayed as a destroying the ‘Old Town’ heritage sites in the pursuit of capital (Miéville 162). From materials of glass and steel to its destructive replacement of the old city, the financial buildings of Ul Qoma mirror the description of postmodern architecture posited by Jameson. Existing underneath the ground level of the city, the concrete transit system is safe from this form of replacement. However, Miéville details that the neoliberal Ul Qoman government has covered up its concrete with the “incoherent, sometimes splendid” pastiches of a diverse range of art styles, including “a camp mimicry of Nouveau” and “a patchwork of Constructivist lines and Kandinsky colours” (200–201). When read alongside Jameson, this renovation reads as an attempt to hide the utopianism of state infrastructure with a project defined by a postmodern trope: the amalgamating of art styles from disparate locations and time periods, removing their context to render them as purely aesthetic.

Yet, in placing a façade over the reminder of the state’s utopian potential, it is insinuated that the postmodern signifiers of neoliberalism are unable to erase it. Citizens still rely on it for transport (Borlú uses it throughout the narrative) and it physically underpins the city. As such, whilst edifices of neoliberalism dominate the surface of Ul Qoma (through postmodern architecture), the transit system’s continued structural existence suggests that utopian potential remains.

Whilst neoliberalism conveys an aesthetic of strength, the memory of the state ‘haunts’. Jacques Derrida’s concept of “hauntology” (1993) posits that there is not a specific temporal or historical origin for ideologies and those dominant in the past exist amongst present conditions, ready to gain purchase (45, 107–108). A haunting socialist past is alluded to when Borlú notes “[the] cliché was that in older offices there was always a faded patch . . . where erstwhile brother Mao had once beamed” (Miéville 194). Viewed in relation to hauntology, this quotation communicates the permeation of Marxist ideologies throughout the cityscape of Ul Qoma. As brutalist architecture underpinning the systems of the city, the Ul Qoma metro infrastructure can be viewed as sharing this haunting potential. As such, despite its best efforts the contemporary, capitalist realist Ul Qoma is not capable of erasing the utopian potential of statist governance; it exists just below the surface and haunts in spaces of absence.

In Authority, concrete, modernist architecture is similarly involved with the process of haunting. Yet, rather than suggesting a potential return, it conveys the (lost) utopian potential of the state. Set in the contemporary United States, the majority of the narrative is contained within the Southern Reach research facility. VanderMeer elaborates on how Southern Reach operates, presenting the organization as structurally dysfunctional. This fallibility is exemplified in descriptions of its architecture. The brutalism of Southern Reach’s architectural design is outlined at the beginning of the narrative, with Control noting its idiosyncrasy:

Built in a style now decades old, the layered, stacked concrete was a monument of a midden – he couldn’t decide which. The ridges and clefts were baffling; the way the roof leered slightly over the rest, made it seem less functional than like performance art or abstract sculpture on a grand and yet numbing scale. (VanderMeer 27)

In this description, the building is presented as impressive yet ghastly. It is a “monument” that is “grand” and “baffling” whilst being a “numbing” “midden”, that is “less functional than . . . abstract sculpture” (VanderMeer 27). Control subsequently notes that the design “had at one time been new” (28). Control’s reaction to the architecture of Southern Reach arguably denigrates modernism and its philosophical concerns with imagining new alternatives to the present (Childs 15). The abstract, monumental spectacle of the building, rather than facilitating a dialectic about modernity and ‘the new’, results in confusion and then apathetic ‘numbing’. By detailing that the building “had at one time been new”, it is conveyed that designs concerned with ‘newness’ are themselves now antiquated (VanderMeer 27–28). Thus, the relationship between Control and the building ultimately demonstrates how, within the logic of neoliberalism, imagining ‘the new’ is anachronistic.

This outdating of futurity also exists in the interior design of the government building. When Control first enters its expedition wing, he is struck by the décor: “A texture and tone that might once have been futurist but now felt retro-futurist clung to white and black furniture that had an abstract modernist quality . . . all this could have come from the set of a low-budget 1970s sci-fi movie” (VanderMeer 166–167). The retro-futurist interior of Southern Reach signals to the crises of state infrastructure in neoliberal countries of the global north. In the economic history of the United States, the 1970s is the last decade before the implementation of neoliberalism (Harvey 39). In having an interior that is retro-futurist and evocative of the 1970s, it is implied that Southern Reach is relying on the same state-funded infrastructure from its inception, a consequence of neoliberal diminution of the state.

In addition to this materialist interpretation, the “1970s sci-fi movie” aesthetic of Southern Reach can be seen to demonstrate how neoliberalism has narrowed conceptions of what potential futures can look like (VanderMeer 167). Combining Derrida’s hauntology with the “slow cancellation of the future” under neoliberalism posed by Berardi, Fisher describes contemporary societies as pining for “lost futures” (Ghosts of My Life 1). For Fisher (2014), nostalgia for the culture of past historical periods, such as the 1970s, represents a collective desire for “a world in which the marvels of communicative technology could be combined with a sense of solidarity much stronger than anything social democracy could muster” (Ghosts 63). According to Fisher, what haunts late capitalist societies in the Derridean sense is a version of the present that has the same technological capabilities without the decline in collectivism engendered by neoliberalism.

From a lack of state funding, the expedition wing of the Southern Reach has come to resemble a future that has been mediated through imagined versions of a pre-neoliberal past, the 1970s. Read in relation to Fisher’s interpretation of nostalgia, the retro-futurist interior of the Southern Reach headquarters thus demonstrates the haunting of a lost future. Combining this analysis of the interior with that of its exterior, this infrastructure provides an aesthetic representation of the relationship between the state’s utopian visions and neoliberalism. The architecture of the Southern Reach headquarters, and Control’s subsequent response to them, demonstrates that in the contemporary context of Authority, past state projects concerned with investigating the unknown are now deemed anachronistic. Their subsequent underfunding has left them as vessels for people to imagine impossible lost futures. Hence, unlike the Brutalism of Miéville, the haunting potential of VanderMeer’s architecture does not suggest that political change can occur. Instead, the interior and exterior aesthetics of this infrastructure communicate an inability to imagine ‘utopia’.

Examining the modernist aesthetics of infrastructure in The City and The City and Authority, it is apparent that they communicate possible futures, distinct from the neoliberal present. In both Weird fiction narratives, the potential of state is dormant. Yet, in The City and The City, signifiers of modernity and utopianism continue to underpin the systems of the city, suggesting a radical alternative. Authority diverges from this: the lost futures which haunt its infrastructure convey the impossibility of achieving an alternative utopian future.

Conclusion

In examining the presence of infrastructure within Jeff VanderMeer’s Authority and China Miéville’s The City and The City, it becomes possible to understand how these objects inform the experience of citizen within a society. Government buildings, public transport systems and roads are objects with political aesthetics. They facilitate discourses surrounding the possibility of achieving alternative futures. Despite their perceived mundanity, their influence on the subject can be radical, revealing power dynamics with the state – infrastructure is weird.

As research in the emerging field of Infrastructure Studies develops, it is important that its critical framework is applied in the analysis of literature and the literary canon. However, with its ruptures of experience and concerning transformations of the material, to best understand the political and experiential effects of infrastructure and its representation within literature, one should begin with examining the Weird.

Citation

Dave Owen, “Neoliberal Façades, Concrete Utopias: The Infrastructure of Weird Fiction,” Alluvium, Vol.9, No.4 (2021): n.pag. Web 6 September 2021. DOI: https://doi.org/10.7766/alluvium.v9.4.05

Contributor Attribution

Dave Owen is a Masters graduate in Twentieth and Twenty-First Century Literary Studies from Durham University, currently based in Newcastle upon Tyne. His research interests include The Weird, infrastructure studies as well as the intersection between political aesthetics, experience and utopianism. Dave’s MA dissertation examined contemporary weird fiction as an ideological critique of neoliberalism. Presently, Dave works in customer service and aims to continue his research at PhD level in the near future.

Works Cited

Anand, Nikhil, Akhil Gupta and Hannah Appel. “Temporality, Politics, and the Promise of Infrastructure.” The Promise of Infrastructure. Eds. Nikhil Anand, Akhil Gupta and Hannah Appel. Durham: Duke UP, 2018, 1–38.

Childs, Peter. Modernism. 3rd ed. London: Routledge, 2017.

Cambridge Dictionary. “Infrastructure Definition: 1. the Basic Systems and Services, Such as Transport and Power Supplies, That a Country or Organization Uses in order to Work Effectively.” Cambridge Dictionary, 4 Aug. 2021, dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/infrastructure.

Derrida, Jacques. Spectres of Marx. London: Routledge, 2006.

Fisher, Mark. The Weird and The Eerie. London: Repeater, 2016.

—. Ghosts of My Life: Writings on Depression, Hauntology and Lost Futures. Alresford: Zero Books, 2014.

Harvey, David. A Brief History of Neoliberalism. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2007.

Jameson, Fredric. Postmodernism, or, The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism. Durham: Duke UP, 1991.

Larkin, Brian. “Promising Forms: The Political Aesthetics of Infrastructure.” The Promise of Infrastructure.Eds. Nikhil Anand, Akhil Gupta and Hannah Appel. Durham: Duke UP, 2018, 175–202.

Marshall, Kate. “The Old Weird.” Modernism/Modernity. 23.3 (2016): 631–649. Doi:10.1353/mod.2016.0055.

Martin, Theodore. Contemporary Drift. New York: Columbia UP, 2017.

Miéville, China. The City and The City. London: Pan Macmillan, 2009.

Mould, Oli. “Brutalism Redux: Relational Monumentality and the Urban Politics of Brutalist Architecture.” Antipode. 49.3 (2017): 701–720. doi:10.1111/anti.12306.

VanderMeer, Jeff. Annihilation. London: Fourth Estate, 2014.

—. Authority. London: Fourth Estate, 2014.

—. Acceptance. London: Fourth Estate, 2014.

Wick, Elvia. “Toward a Theory of the New Weird.” Literary Hub, 5 Aug. 2019, lithub.com/toward-a-theory-of-the-new-weird/?single=true. Accessed 15 July 2021.

Hyperlinks

For Elvia Wick “Toward a Theory of the New Weird”: Toward a Theory of the New Weird ‹ Literary Hub (lithub.com)