Caroline Edwards and Ben Worthy

As part of Birkbeck’s Arts Week 2017, we organised a panel titled "Will 2017 be 1984" (you can listen to a podcast recording of the panel here) which considered the uncanny relevance of Orwell’s novel for our own times in an era of post-truth. Earlier this year, sales of Nineteen Eighty-Four surged (and the novel became an Amazon bestseller) after Trump’s advisor Kellyanne Conway used the Orwellian term “alternative facts” in an interview. Meanwhile, Margaret Atwood's dystopian novel The Handmaid's Tale (1985), a novel that was written as a direct response to Orwell's influential text, has similarly seen a dramatic boost in sales since the Trump administration came to power. Atwood’s novel has been adapted into a series for American TV by the streaming service Hulu, which premiered in April 2017. As she has recently said in interview, The Handmaid’s Tale is enjoying a disturbing and anachronistic revival under Trump: "It’s back to 17th-century puritan values of new England at that time in which women were pretty low on the hierarchy" (Atwood qtd in Reuters, n. pag.) Atwood’s novel has even inspired political activists in the past few months – women marching on the Women’s March in January 2017 held signs that read, “Make Margaret Atwood Fiction Again….”

Given the prevalence of dystopian fiction to the disturbing political realities in 2017, we decided to reconsider the literary genre of dystopia, and Orwell's Nineteen Eighty-Four in particular, to try and think through the relationship between utopian dream and dystopian nightmare that dystopian texts have articulated throughout the twentieth century.

On the eve of the outbreak of the Second World War, an ageing H. G. Wells visited Australia, delivering two lectures that were broadcast on Australian radio. In his lecture on "Utopias," he remarked that "[t]hroughout the ages the Utopias reflect the anxieties and discontents amidst which they were produced. They are, so to speak, shadows of light thrown by darknesses" (1982: 117). Wells recognised the intrinsic connection between utopian dreams and the "dark" conditions that inspire writers to venture into the realms of the speculative imagination. Indeed, many of Wells’ major works themselves explore how the vision of the good society that is, as Thomas More’s coinage dictates, "no place" can slide into its dystopian counterpart. The Time Machine (1895) initially strikes the Time Traveller as a pastoral Arcadia until he comes to understand that the graceful, childlike Eloi are, in fact, fatted cattle for the troglodytic labouring Morlocks. The Sleeper Awakes (1910) also plays with utopian form, building on William Morris’ premise of miraculously waking up in the utopian future in News From Nowhere (1890). However, instead of waking up in a world of social equality, Wells’ protagonist Graham discovers that the technologically advanced world of 2100 has evolved into a distinctly anti-utopian capitalist society of "higher buildings, bigger towns, wickeder capitalists, and labour more down-trodden than ever" (Wells 2016: 591).

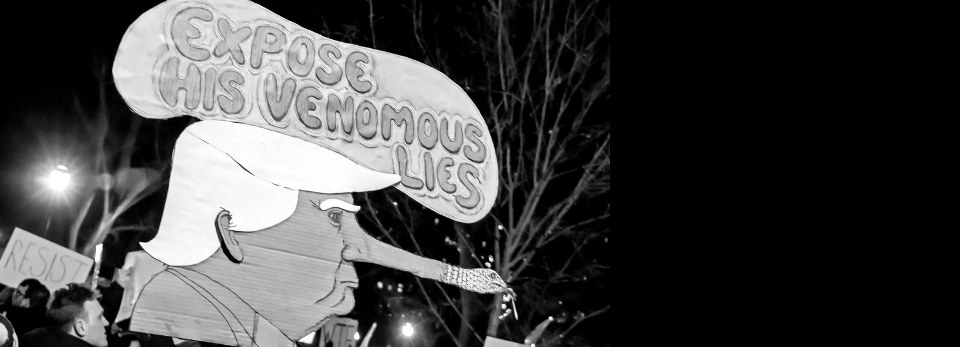

Will 2017 be 1984? With his attacks on "fake media" and use of "alternative facts" the election of Donald Trump reveals an increasingly Orwellian reality

[Image by Meschae Studios under a CC BY license]

Although it had been coined by John Stuart Mill in 1868, the term "dystopia" came to be used to describe speculative visions of the future that lacked the optimism of utopia’s "good society." After a boom in utopian novels of the fin de siècle, the focus on socialist visions of the collective future slid into a palpable fear of the kind of modernity that technology could deliver and the loss of liberal values implied in enforced collectivisation. The extraordinary popularity of H. G. Wells’ utopian visions in novels such as A Modern Utopia (1900) and Men Like Gods (1923) provoked satirical responses among his contemporaries. As he explained in 1947, E. M. Forster conceived of his futuristic speculative story "The Machine Stops" (1909) as a "reaction to one of the earlier heavens of H. G. Wells" (1947: vii), which has degenerated into a dystopian nightmare. The techno-utopianism of Wells’ Men Like Gods similarly inspired Aldous Huxley’s eugenicist dystopia, Brave New World (1932). In 1962, Huxley recalled his frustration with Wells’ utopian adventure story: "Men Like Gods annoyed me to the point of planning a parody, but when I started writing I found the idea of a negative Utopia so interesting that I forgot about Wells and launched into [Brave New World]” (Huxley in Collins 1973: 41). As Huxley cited the Russian philosopher Nicolas Berdiaeff’s in the epigraph to Brave New World, "Utopias seem much more attainable than one may have previously thought. And we are now faced with a much more frightening thought: how do we prevent their permanent fulfillment?" (Berdiaeff in Huxley 1994: n.pag.).

In the 1930s, then, science fiction became increasingly concerned with using its speculative mode to examine the dangers of fascism. The growing presence on the international stage of Hitler’s Nazism led many writers to consider the dystopian realities of wholesale attempts at social engineering; something which had plagued the utopian novel since More’s construction of the ideal humanist society in Utopia (1516)—which, of course, had included an authoritarian monarch and also slavery. Written during the early years of the Great Depression in the 1930s, Huxley’s dystopia anticipates the inequality of Orwell’s Oceania, with the dehumanizing triumph of Western capitalism in the year 632 A.F. (“After Ford”).

If Huxley’s eugenicist vision of "achieved utopia" in Brave New World anticipated the popularisation of Fascist ideology in Germany in the 1930s, the dangers of the Nazi cult of masculinity was challenged in a different way by a number of feminist anti-fascist dystopias. Naomi Mitchison’s We Have Been Warned (1935) is set in the interwar period of the early 1930s, revealing the possible future of a fascist Britain; an ideology which she describes in The Home and a Changing Civilisation (1934) as "this final and peculiarly revolting end-form of capitalism" (102). Storm Jameson’s In the Second Year (1936) similarly brings German fascism closer to home in a vision of a Britain colonised by fascism; as do Ruthven Todd’s Over the Mountain (1939) and Winifred Holtby’s play Take Back Your Freedom (1939). Katharine Burdekin’s Swastika Night (1937) (published under the pseudonym of Murray Constantine) offers a more chilling vision of fascist domination from the perspective of more than 700 years in the future of Hitler’s Thousand Year Reich.

From utopian dream to dystopian nightmare: the popular utopian novels of H. G. Wells inspired writers such as E. M. Forster and Aldous Huxley to produce dystopian responses to Wells' vision of the future

[Image by John Keogh under a CC BY-NC license]

But it is George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949) that has had the most lasting influence on the dystopian imagination. In the near future 1980s, Britain has become Airstrip One, an outpost of the empire of Oceania (one of three global super-states, all of which are collectivist). WWII led to an atomic war in the 1950s and by the 1960s English Socialism has become Ingsoc and won the Revolution to overthrow the capitalists, about whom no one can recall anything other than their quaint top hats. Ingsoc is presided over by a Stalin-like leader known as Big Brother, whose ubiquitous face is described as offering "heavy calm, protecting: but what kind of smile was hidden beneath the dark moustache?" (107).

What is so striking about Orwell’s dystopian vision is the combination of high-tech surveillance with the decidedly low-tech setting of decaying Victorian architecture, electricity shortages, and impoverished, rat-infested slums. Orwell’s near-future London is in a permanent state of war, suffering Blitz-style bombings and wartime rationing whilst its citizens live under the microscopic watch of complete state surveillance. The capital is described as "vast and ruinous, [the] city of a million dustbins" (77), where everything smells of boiled cabbage and people with decaying teeth trudge around in leaky shoes, darning old socks, bartering, and trying to fix their broken plumbing. The state’s Huxleyesque synthetic food—saccharine tablets, grey stews of meat substitute, and oily gin—is countered by a black market of real coffee, chocolate, butter, and cigars. The novel is focalised through Party worker Winston Smith, whose work at the Ministry of Truth involves rewriting records and newspaper articles in a ceaseless effort to control the official historical record. As people are murdered or disappear into the shadowy police state (a process known as "vaporisation"), an army of bureaucrats like Winston must rewrite events to obliterate their record of ever having existed. Orwell’s friend Arthur Koestler had covered similar ground in his influential account of Stalin’s purges in Darkness at Noon (1940), which depicts the final collapse of Russia’s early revolutionary utopianism during "the Terror" as Stalin’s police state murdered Bolsheviks and proceeded to airbrush their existence out of official recorded Soviet history. Likewise, Winston bears witness to the airbrushing of history. "[I]t was not even forgery,” he thinks, “[i]t was merely the substitution of one piece of nonsense for another" (43). Only fragments of memories and ideas exists to counter the official history and claim of the Party, as when Smith dreams of freedom in a country idyll an wakes up with the name "Shakespeare" on his lips.

For the modern reader, the book is replete with contemporary resonance. The leaders in Oceania control their people through targeted hatred and predict what they do before they do it. There are uncomfortable echoes of the dark side of a surveillance society and big data: the secret police can even monitor you through your television. Double-think dominates a world where those in power can believe contradictory things simultaneously and bend reality at will. Opening up Orwell’s book today, Oceania’s propaganda slogan "ignorance is strength" rings far too familiar for comfort. However, the real warning of the novel concerns the destruction of objective reality and loss of humanity and sense of self that it brings. The world of Winston Smith is one where, aside from one fleeting incident, it is impossible to know if past events ever took place or what is truly happening in the present: when Smith opens his illicit diary he is unsure even of the exact date. This uncertainty leaves the inhabitants of Oceania adrift, left only with a feeling in the pit of their stomach that this world is not somehow right. As Ben Pimlott argued, Orwell’s dystopia hinges upon a very modern conundrum:

The novel can be seen as an account of the forces that endanger liberty and of the need to resist them. Most of these forces can be summed up in a single word: lies. The author offers a political choice—between the protection of truth, and a slide into the expedient falsehood for the benefit of rulers and the exploitation of the ruled, in whom genuine feeling and ultimate hope reside. (n.pag.)

Exactly such insulation was attempted by the Nazis and Stalin’s Soviet regime, both of which sought to create their own "moral universe" where laws of science, historical knowledge and objective reality were subsumed by ideology, from Goebbels' famous claim that Jesus wasn’t Jewish to attempts in the USSR to make biology fit with Marxist dialectical patterns (Overy 2004). Primo Levi spoke of how the guards in the camp would torture inmates with the idea that no one in the future would ever believe the victims (Levi 1989).

Frighteningly recognisable: Orwell's classic text outlines an authoritarian future state whose surveillance technology has become reality in the 21st century

[Images by Anton Raath under CC BY-SA licenses]

Orwell wrote in 1942 of how he feared just such a pattern of falsehood subsuming objective reality. In his reflections on the distortions and lies around the Spanish Civil War he outlined his fear that "the very concept of objective truth is fading out of the world" (1970: 258). He imagined "a nightmare world in which the Leader, or some ruling clique, controls not only the future but the past… if the Leader says of such and such an event, 'It never happened'—well, it never happened. If he says two and two are five… two and two are five. This prospect frightens me much more than bombs" (Orwell 2004, 170). It is a prospect that also carries down to us in a world of fabricated events, denial of self-evident truths and "alternative facts."

The distortion of reality reaches its terrifying endpoint when Smith, being tortured in the Ministry of Love by his erstwhile protector O’Brien, is made to believe two plus two equals five and that Oceania has always been at war with Eastasia. He then asks if Big Brother is a real person:

Smith: Does Big Brother exist?

O’Brien: Of course he exists. The Party exists. Big Brother is the embodiment of the Party.

Smith: Does he exist in the same way as I exist?

O’Brien: You do not exist. (Orwell 1990: 271-2)

In Nineteen Eighty-Four we find a new incarnation of the dystopian vision of techno-modernity that Yevgeny Zamyatin had memorably invoked in We (My) (1924), but updated to match the context of post-WWII economic depression in Britain. As we have already seen, it is common for dystopian novels to reflect upon utopian dreams and attempts at social engineering. Here, Orwell stages the utopian dream of socio-economic equality, with its concomitant reduction of the length of the working day and an envisioned life of plenty for all workers; the dream that Wells conquered through scientific innovation in A Modern Utopia and Men Like Gods. In the war-torn history of Oceania, however, the capitalist manufacturing problem of over-production has triumphed over the utopian socialist dream of reducing hard toil in favour of pleasurable, socially productive labour.

Many reading Nineteen Eighty-Four were struck by the novel’s terrifying realism and familiarity: so much so that readers of illegal copies snuck behind the iron curtain believed the book to have been written by someone close to Stalin (Hitchens 2002). However, despite its apparently Soviet contours (with Big Brother’s Stalinist cult of personality and the destruction of individualism in favour of collectivism), Orwell’s totalitarian state actually represents a much more capitalist vision of the future than is usually acknowledged, in line with the critique of capitalism found in the earlier utopias of Wells, Bogdanov, and Tolstoy. Orwell himself had insisted that Nineteen Eighty-Four had been written "against totalitarianism and for democratic Socialism, as I understand it" (Orwell 1970: 28). Thus, as Winston reads in Goldstein’s text-within-the-text, the "idea of an earthly paradise in which men should live together in a state of brotherhood, without laws and without brute labour […] had been discredited at exactly the moment when it became realisable" (Orwell 1990: 212-13).

As Winston’s surrender at the end of Nineteen Eighty-Four shows us, the resonant power of dystopian novels lies in their fraught relationship with utopian dreaming. Zamyatin’s We, Huxley’s Brave New World, Burdekin's Swastika Night and Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four thus force the reader, as Erica Gottlieb suggests, to consider "how an originally utopian promise was abused, betrayed, or, ironically, fulfilled so as to create tragic consequences for humanity" (8).

CITATION: Caroline Edwards and Ben Worthy, "Will 2017 be 1984?," Alluvium, Vol. 6, No. 2 (2017): n. pag. Web. 31 May 2017, DOI: https://doi.org/10.7766/alluvium.v6.2.03.

Works Cited:

Collins, Christopher. Evgenij Zamjatin: An Interpretive Study. The Hague: Mouton, 1973.

Forster, E. M. "Introduction." In: Collected Short Stories. London: Sidgwick and Jackson, 1947.

—. The Machine Stops. London: Penguin Classics, 2011.

Gottlieb, Erica. Dystopian Fiction East and West: Universe of Terror and Trial. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2001.

Hitchens, Christopher. Why Orwell Matters. New York: Basic Books, 2002.

Huxley, Aldous. Brave New World. London: Flamingo, 1994.

Koestler, Arthur. Darkness at Noon. Translated by Daphne Hardy. London: Vintage, 2005.

Levi, Primo. The Drowned and The Saved. London: Abacus Books, 1989.

Mitchison, Naomi. The Home and a Changing Civilisation. London: John Lane, 1934.

Morris, William. News From Nowhere and Other Writings. Edited by Clive Wilmer. London: Penguin, 2004.

Orwell, George. Nineteen Eighty-Four. London: Penguin, 1990.

—. Shooting An Elephant and Other Essays. London: Penguin, 2004.

—. The Collected Essays, Journalism and Letters of George Orwell, Volume 2. My Country Right or Left 1940-1943. Edited by Sonia Orwell and Ian Angus. London: Harmondsworth, 1970.

Overy, R. J. The Dictators: Hitler's Germany and Stalin's Russia. London: WW Norton & Company, 2004.

Pimlott, Ben. "Introduction to 1984." Orwell Foundation, 2000: https://www.orwellfoundation.com/the-orwell-prize/orwell/resources/ben-pimlott-introduction-to-nineteen-eighty-four/ (Last accessed 25 May 2017).

Reuters. “Margaret Atwood: The Handmaid's Tale sales boosted by fear of Trump.” The Guardian, 11 February 2017. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2017/feb/11/margaret-atwood-handmaids-tale-sales-trump (Last accessed 30 May 2017).

Wells, H. G. A Modern Utopia. Edited by Gregory Claeys. London: Penguin, 2005.

—. Experiment in Autobiography: Discoveries and Conclusions of a Very Ordinary Brain (since 1866). London: H. G. Wells Library, 2016.

—. Men Like Gods. London: Sphere Books, 1976.

—. The Sleeper Awakes. Edited by Patrick Parrinder. London: Penguin, 2005.

—. “Utopias” [transcript of ABC radio broadcast, 19 January 1939]. Science Fiction Studies, Vol. 9, No. 2 (1982): 117-121.

Please feel free to comment on this article.