Christina Scholz

Karen Mirza and Brad Butler’s 2012 film project Deep State, scripted by China Miéville, tells the story of a time traveller who passes through holes in conventional history created by the irruptive power of riots. Formally it oscillates between cinema and drama in that it incorporates archive footage as well as theatrical elements. The collage-style editing technique establishes a relationship between non-fiction, fiction and semi-fiction and can also be read as a deliberate nod to another seminal experimental time travel film, Chris Marker’s La Jetée from 1962. Its title is a reference to a “state within the state,” “allegedly manipulat[ing] political and economic policy to ensure its interests within seemingly democratic frameworks” (Mirza and Butler 2012; film description on Vimeo). In the context of the Arab Spring, this term has also been used to describe politics in Egypt. The editing and selection of news footage used in the film also stress the influence of the United States in what are essentially Egyptian affairs.

Cinema or drama? Mirza and Butler’s Deep State incorporates archival footage as well as theatrical elements, with a collage-style editing technique

[Video available on Vimeo]

Mirza and Butler state that Deep State is political theatre applied to film (Khanna 2012, n.pag.), that is to say Augusto Boal‘s poetics of the oppressed, which he himself defines as “essentially the poetics of liberation” (155). Ever since ancient Greek drama, a barrier has existed between actors and spectators. This barrier must be destroyed: “all must act, all must be protagonists in the necessary transformations of society” (Boal x). This is what Boal calls the poetics of the oppressed, the conquest of the means of theatrical production. Thus, “the people reassume their protagonistic function in the theater and in society” (119; emphasis added). The aim is to “change passive spectators into active participants” (Boal 122)—not catharsis as in Aristotelian theatre, or inducing the awakening of a critical consciousness as in Brecht. The former spectator now assumes the role of protagonist, “changes the dramatic action, tries out solutions, discusses plans for change—in short, trains [her]self for real action. In this case, perhaps the theatre is not revolutionary in itself, but it is surely a rehearsal for the revolution” (Boal 12).

DEEP STATE: The Revolution Will Not Be Televised Weaponized

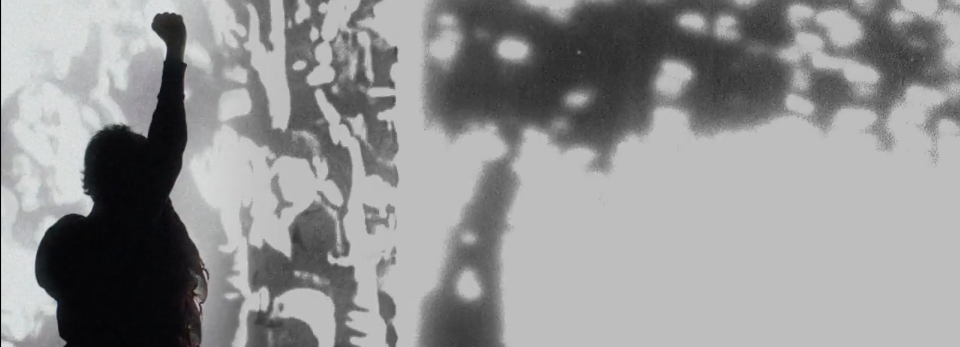

Deep State‘s opening sequence establishes that the film itself is from the future, invading the audience’s hacked TV programme—to show them, us, in a thematic parallel to Ray Bradbury’s short story “The Toynbee Convector” (1984), where we can get, what we can achieve if we realize our revolutionary potential. The destruction of the television set in this sequence already hints at Boal’s argument that action must replace the spectacle. We, the spectators, must become protagonists. The nameless protagonist who will lead us there is presented as a riot time traveller who has realized that crisis creates portals (Deep State 17:03). We are confronted with a dense collage of news footage showing international riots, uprisings across time, moments of crisis which render the membrane of space-time permeable. Any one revolution becomes every possible revolution, unlocking potential. The protagonist seems to not just take part, but to initiate protest: in a sort of call-and-response scene he raises his fist before the figure in the archived material does (Deep State 07:38). The protagonist does not speak. The only text we have is presented via voice-over and interruptions, quoting various sources, including the Egyptian Activists’ Action plan (or “How to protest intelligently”) that was circulated as early as January 2011 (Madrigal 2011), telling protesters where to assemble, what to wear, and how to protest violence-free.

The protagonist raises his fist (07.38).

[Image used under fair dealings provisions]

In addition we have the character of the language teacher. She functions as what Augusto Boal calls “the Joker,” who provides explanation from the filmmakers’ point of view. The Joker is a character removed from the other characters, closer to the spectator. A contemporary mediator, offering analysis, and in this case, teaching language. In Boal, “all possible languages,” or language systems, include theatre, photography, puppetry, film, and journalism (Boal 121). He also emphasizes the body as the theatre’s most basic tool and element. So-called image theatre speaks through images made with the actors’ bodies (126), letting those bodies express themselves rather than imposing meaning on them. Moreover, according to Boal, the combination of roles that a person must perform imposes on [her] a “mask” of behaviour (127). In the Theatre of the Oppressed, and thus in Deep State, these quotidian masks—the masks of class, of occupation, of gender, of religious and ethnic identity—are cast off. What remains and is expressed, foregrounded, is the human factor.

Without what Boal calls “masks,” what we see is what we get. Expression through the body is more direct and less ambiguous than expression through language. The language teacher in Deep State is a black woman—which would, more often than not, denote a marginalised character—but she refuses to be marginalised. She is also unarmed—and the editing places her at the heart of every, that is to say, any uprising. In Boal’s “image theatre” the production of transitional images is encouraged “to show how it would be possible to pass from one reality to the other” (Boal 135), from the actual image (i.e. our experience of a situation) to the ideal image or state. In the language of film, the transition is employed on the formal level (the collage-like montage) as well as on the diegetic level (time travel through riots), thus foregrounding the revolutionary element in both ‘film theatre’ and human history.

Image theatre is described in Boal as having a capacity for making thought visible. This happens because use of the language idiom is avoided (Boal 137-8). In Deep State there is an additional factor of estrangement and disruption, as the character of the language teacher does not speak at first. Instead, it is her body that speaks for her. Using gestures and facial expressions and adding single syllables, she works her way towards language, repeating four phonetic phrases reconstructed from Arabic meaning, which are not subtitled or translated: “hold your ground,” “Egyptians,” “homeland” and “strike” (Mirza qtd. in Khanna 2012, n.pag.). The antagonist, finally, is the highly abstract Deep State, using “interrogation techniques” employed by the CIA on the imprisoned protagonist. The torture or “monster” scene is based on the Torture Memos, sometimes called the Bybee Memo or 8/1/02 Interrogation Opinion, a US Justice Department memo that was leaked in 2009, detailing “interrogation techniques […] for use on a top Al Quaeda detainee,” including waterboarding and cramped confinement “with insect: for detainee known to have phobia” (Watkins 2014). [1]

The protagonist watches the protests, his face illuminated by the screen (18.39).

[Image used under fair dealings provisions]

In Deep State, close-ups of the protagonist’s eyes watching the protests, with the light from the television playing on his face, turn him into a spectator as well, which provides one level of identification. Moreover, the voice-over uses the first-person “I” and second-person “you” interchangeably—enabling further identification of the audience with the protagonist—preparing us to take over from him (Boal 1979). Finally, the interruptions and the collage editing create dissonance and unrest, while the on-screen violence and the foregrounding of the human factor, especially through the character of the language teacher, create empathy. In the end, the protagonist and the language teacher merge (she is wearing his space suit and scarf)—combining the teaching and the protest to form a synthesis: teach protest. Again, this recalls the Egyptian protesters’ leaflet on “How to protest intelligently,” which is inserted in-between scenes throughout the film.

Occupy TV, Occupy Cinema

Following Walter Benjamin, one could argue that by subtracting the dynamic aspect and the unrepeatability of a dramatic performance, the theatrical scenes in Deep State lose much of their immediacy and impact—including the audience’s possibility to interact with the characters on stage (as suggested by Boal), interpreting the action and suggesting alternative solutions. These actions now only occur in the audience’s imagination, they remain theoretical—until taken into the outside world. The film’s technique would facilitate a re-imagination as a dramatic performance, with the archive footage (back-)projected onto the backdrop, so that the separate spaces that come together through editing in the film are actually brought together in the same physical space on stage. But if we stick to Boal’s original argumentation, a re-adaptation is unnecessary, since the techniques employed in Deep State may be better suited to contemporary audiences and contemporary technology: The conventions of theatre, he argues, are created habits (Boal 1979: 167). Different circumstances demand different sets of conventions. The aim is not to destroy theatre but to enrich it, which requires a flexible structure (177). Paraphrasing George Ishikawa, Boal states that the bourgeois theatre is finished theatre (142). In contrast, and as a reaction to that, his Theatre of the Oppressed is an open discourse, presenting images of transition (Ibid.). We, the audience, are no longer observers of the ready-made spectacle but protagonists in an experiment, a rehearsal [of change, of revolution].

As the voice-over in Deep State says: “I expect more after all this than images of change” (Deep State 04:10) and “in my opinion, TV and cinema are occupied by the enemy” (Deep State 35:30). This takes us back to the image of the destroyed television set used in the opening sequence and basically calls upon theatre, the Theatre of the Oppressed, to occupy television, to occupy cinema. Theatre must be accessible to all, including those who cannot afford to pay for tickets. Deep State‘s creators put the full version of the film on Vimeo, so that it can be streamed for free. This makes it not only repeatable but distributable, freely available to everyone. This is theatre for the masses.

“I expect more after all this than images of change.”

[Image used under fair dealings provisions]

Heroes Я Us

To Boal it does not matter that the spectator-turned-protagonist’s action is fictional; what matters is that it is action (Boial 1979: 122). “[T]he spectator-actor practises a real act even though [s]he does it in a fictional manner” (141). Giving examples from image theatre exercises with groups of exploited workers, Boal shows that “[t]he rehearsal stimulates the practice of the act in reality” (142). “It is not the place of the theater to show the correct path,” he states, “but only to offer the means by which all possible paths may be examined” (141), thus linking it closely to the conventions of science fiction. Moreover, the torture scene clearly shows that the means of expression and of interaction are not yet in the hands of the people, the audience. The story, their history, is not being written by them—it is still a product of outside forces, be it a repressive government or other states (in this case the United States) interfering in narratives that are not their own.

In a final formal break, a black-and-white animated figure breaks into the action (Deep State 38:14), blackens the camera with spray paint and liberates the imprisoned protagonist. The editing and the “unfinished” quality of the character lead us to interpret him as the spectator-turned-protagonist, stepping onto the stage and into the action. In this context, the warning issued by the voice-over becomes an instruction to the new protagonist, to us: “This way. Quickly. It can come back, it will come back” (Deep State 38:48). But there is no escape, and no escapism, as she adds, “Those forces that torment you have, each of them, a face, address and name” (Deep State 18:30). Then, very directly, to the rescued protagonist, and in a more direct sense to the spectators, to us: “Come outside. Into the street” (Deep State 39:30). In a final twist, Mirza and Butler take the action back to Britain so that a British audience can contextualize their new impulses for themselves, in their culture, their state, their system, as an actual British pedestrian (whose face is never shown on-screen) tells an interviewer that “the government have never ever really been in touch” (Deep State 43:05) and adds examples of and comments on police violence and injustice. “You can’t live like that. You can’t” (Deep State 44:10).

As the voice-over tell us to “get rid of the body, the state and its deeps” (Deep State 44:13), it leaves us with this notion from Boal’s Theatre of the Oppressed: “It is not the hero who must be belittled; it is his struggle that must be magnified. Brecht sang: ‘Happy is the people who needs no heroes.’ I agree. But we are not a happy people: for this reason we need heroes” (Boal 1979: 190). And of course, these heroes must be ourselves.

CITATION: Christina Scholz, “Deep State and the Future of Theatre,” Alluvium, Vol. 6, No. 2 (2017): n. pag. Web. 31 May 2017, DOI: https://doi.org/10.7766/alluvium.v6.2.02.

Christina Scholz is currently writing her PhD thesis on M. John Harrison’s Kefahuchi Tract trilogy. Her fields of interest include China Miéville’s fiction, the further theorisation of Weird Fiction, Hauntology and the Gothic imagination, the interrelation of genre fiction and other forms of art, and depictions of war, violence and trauma in the arts. Her Master’s thesis, Thanateros: (De)Konstruktion von männlichen Heldenbildern im Mainstream-Film, has been published by AV Akademikerverlag in 2012. She is a regular reviewer for Strange Horizons.

Christina Scholz is currently writing her PhD thesis on M. John Harrison’s Kefahuchi Tract trilogy. Her fields of interest include China Miéville’s fiction, the further theorisation of Weird Fiction, Hauntology and the Gothic imagination, the interrelation of genre fiction and other forms of art, and depictions of war, violence and trauma in the arts. Her Master’s thesis, Thanateros: (De)Konstruktion von männlichen Heldenbildern im Mainstream-Film, has been published by AV Akademikerverlag in 2012. She is a regular reviewer for Strange Horizons.

Notes:

[1] This document also influenced Miéville’s short story “The 9th Technique”, published in Three Moments of an Explosion in 2015.

Works Cited:

Boal, Augusto. Theatre of the Oppressed. Translated by Charles A. and Maria-Odilia Leal McBride. New York: Theatre Communications Group, 1979.

Khanna, Shama. “Mirza/Butler Interview.” In: Experimenta Weekend: Artists’ Film & Video at the BFI London Film Festival, markwebber.org.uk, 2012: http://markwebber.org.uk/experimenta/2012/09/18/mirza-butler/ (Last accessed 23 May 2017).

Madrigal, Alexis C. “Egyptian Activists’ Action Plan: Translated.” The Atlantic, 27 January 2011: http://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2011/01/egyptian-activists-action-plan-translated/70388/ (Last accessed 23 May 2017).

Miéville, China. “The 9th Technique.” In: Three Moments of an Explosion. London: Macmillan, 2015: 109-19.

Mirza, Karen, and Brad Butler, dirs. Deep State. Scripted in collabortion with China Miéville. Film and Video Umbrella, 2012: http://vimeo.com/41903421. Film.

Watkins, Ali. “Unsettling infographic from @AFP on #CIA’s approved interrogation techniques: http://u.afp.com/YyM.” 3 April 2014, 4:54 PM: https://twitter.com/aliwatkins/status/451734371306078208?lang=en. Tweet.

Please feel free to comment on this article.

Dear Christina Scholz,

I've been searching for reference in the Theatre of the oppressed book. But the name is George Ikishawa in the book not Ishikawa. Mispelling? But I've found no reference to this "Ikishawa" name at all. Do you have any idea who he was in the Theatre scene?