Mark P. Williams

This article will suggest that Alan Moore’s perspective can usefully be considered as part of an underground aesthetic which declares the necessity of solidarity of experience with all other groups through artistic expression. I would like to consider Moore’s earlier epic poem The Mirror of Love (2004) as a pre-text for his more recently completed underground comix project Lost Girls (2006) and, in so doing, situate Lost Girls as a speculative underground comix narrative. Like Moore’s earlier work, The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen (1999-), Lost Girls is what we can call a “counterfiction” (Hills 2003): that is, a text that presents a crossover between well-loved fictional characters, which necessarily always has a radical potential (see my discussion of the radical potential of crossovers, "Rise of the Irregulars"). The characters appropriated into the world of Moore and Gebbie’s Lost Girls, include: Wendy from Peter Pan, Dorothy from the Wizard of Oz, and Alice from Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland / Through the Looking-Glass. In Lost Girls, these canonical protagonists from children’s literature meet as adults in a hotel in Switzerland shortly before the outbreak of WWI to share stories of their respective sexual awakenings. This takes the form that Moore and Gebbie have polemically categorised as pornography, which has itself created some controversy.

Sexual awakenings celebrated and explored in modern works mark a concentrated move away from prudery

[Image by Paul Townsend under a CC BY-ND license]

Produced over many years, the different chapters of Lost Girls present the reader with both a defence of pornography, understood as a genre of human fantasy, and also a text that transforms pornography into another form of Art. In the process Lost Girls works through a catalogue of representations of sexuality, from subconscious desire through to bedroom farce. Moore says of the lengthy discussions between himself and Melinda Gebbie, which underpin every panel of the comic, that: “[w]e’ve had sixteen years to think about all the moral ramifications of Lost Girls, whereas most of our opponents are liable to be a wee-bit rabid and not thinking about the things they say before they say them” (Moore qtd in Gravett 2008: n. pag.). As such the arguments of the text must be read as progressing historically and personally in the same way the stories of the individual characters develop. For this reason, I would like to suggest that the pre-text to Lost Girls – Moore’s poem The Mirror of Love – is particularly relevant to situating Lost Girls, both in terms of its closeness to themes explored in the later text, as well as the milieu in which both texts emerge. Lost Girls sees Moore and Gebbie taking up the concept of the “moral pornographer” from Angela Carter’s 1978 polemical work The Sadeian Woman. This is made explicit by Moore in an interview with Paul Gravett:

Paul Gravett: In The Sadeian Woman Angela Carter saw the potential, and the need, for ‘enriching pornography,’ not two words you normally associate with each other. What are your thoughts on the role and potential of porn?

Alan Moore: Angela Carter’s book did give us some formative thoughts on the matter. She ended the book by suggesting that even though most pornography was disappointing, if not offensive, she could imagine a form of pornography that would be healthy in a cultural sense and enriching and do all of the things that art was capable of doing but in a pornographic context. Simone de Beauvoir in Must We Burn De Sade? makes a similar argument and I believe even Andrea Dworkin, before she died, had at least accepted the hypothetical possibility of a form of pornography that she would see as benevolent. (Gravett 2008: n. pag.)

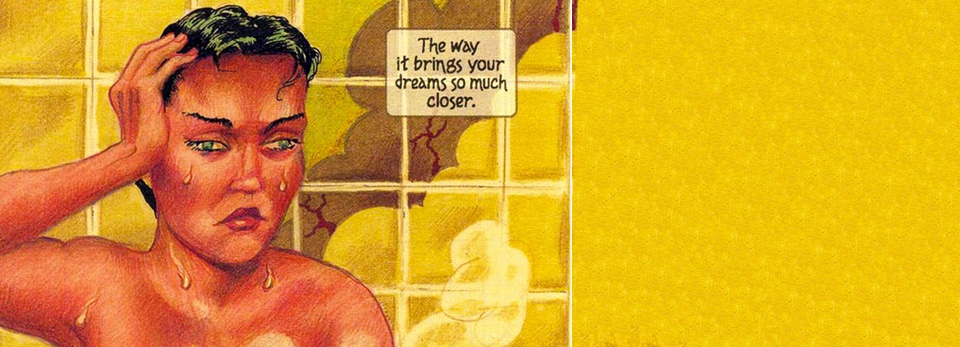

Moore’s stated intentions are complex here and certainly leave open a lot of territory for dispute and debate. However, they offer a useful insight into something that is plainly in evidence throughout the narrative of Lost Girls: a desire to offer sexual exploration, rather than sexual exploitation, as a positive creative act on the part of the text’s protagonists. In this sense, we might read Lost Girls as a positive reworking of the kind of historical energies that, in parallel works such as From Hell (1989-96), can only be imagined destructively. In turn, the publication and export of the text itself has resulted in a swathe of challenges to legal definitions of pornography in the US, Canada, France and the UK. In situating the adventures of Alice, Wendy and Dorothy within an erotogenic paradigm, Moore and Gebbie present a world of constant historical change, already bursting with energies and movements of people and ideologies. As we can see from the panel below, Chapter 5 (“Straight On 'Til Morning”) is a good example of Melinda Gebbie’s bold use of colour to juxtapose Wendy Darling’s bath (inspired by her erotic fantasy) with her husband Harold’s own pornographic dream. The scene of Harold sleeping is rendered in muted colours with an animated materialisation of his sex-dream enacted by two primitively conveyed figures in green, purple and black, whilst Wendy’s experience of masturbating in the bath brings her own dream to vivid life (Moore and Gebbie 2006: 6). This is a narrative world in flux, which has the potential to be both benign and malign and is constantly hovering between the two. The historical events of the build-up to the First World War appear as a counternarrative behind the sensual unfolding and sexual maturation of the three women. The women’s erotic unfolding is intimately followed and matched by the shifts of rhetoric and the imagery with which their personal histories and fantasies are expressed visually; which is then contrasted with the visual narrative of the text’s portrayal of history.

Lost Girls forces its reader to address the concept of pornography, asking how pornography can be read in scholarly terms (Moore and Gebbie 2006: 6)

[Image used under fair dealings provisions]

The journal ImageTexT: Interdisciplinary Comics Studies has conducted a critical roundtable on Lost Girls which makes an essential counterpoint to Moore and Gebbie’s project called “ImageSexT: A Roundtable on Lost Girls: Down the Rabbit Hole.” This scholarly discussion offers a useful overview of the way in which Lost Girls forces its reader to address the concept of pornography reflexively and includes critical discussions and polemical assertions about how pornography can be read in scholarly and critical terms. Because of the pornographic visual narrative of Lost Girls, many reviewers focus on the aspects of this text which problematise the position of the reader as a consumer of pornography. In her essay “History, Pornography and Lost Girls,” Meredith Collins (2007) focuses instead on the aspects of the text which problematise the notion of pornography as a historical category in terms of the eccentricities of the characters:

Curious behavior in this text often seems to be a Freudian symptom of unresolved emotional repercussions from negative sexual situations. This is a highly unusual move within pornography. Instead of giving us a wholly sexual and idealized world, Gebbie and Moore confront us with a complex but thoroughly sexual world in which sexual acts have the power to affect the lives of participants and others. It is crucial not only that sex can hurt or heal, but also that these characters are more than appropriately-orificed mannequins, and that their pornographic world is more unusual for their ability to experience hurt and healing. (Collins, 2007: n. pag.)

Collins does, however, take the view that certain key moments of resolution in the text are relatively poorly handled in terms of their implications about the understanding of sexuality. She finds too much insistence on sex’s healing power and is troubled by Alice, a character who is presented as being staunchly lesbian throughout the majority of the narrative, but then who decides near the conclusion of Lost Girls to experiment with the male hotel owner. In response to this reading, Chris Eklund re-contextualises these sequences of the text in terms of Moore’s relationship with magick, drawing on Eklund’s own experience as a practising magician. He considers the text through the framework of a conception of “working,” which he describes in similar terms to the invocations that Moore gives in his live performances or which suffuse his comic series Promethea (1999-2005). When he describes this, in his title, as “A Magical Realism of the Fuck,” Eklund is referring to the idea of a magician negotiating with the tropes of realism:

As a magician, Moore knows the power of taboo – and of taboo breaking. Moore and Gebbie break certain taboos, and draw the lines of others, in the name of sex as a healthy, healing practice. The mutual ‘want to’ acts as a magical law, similar to Aleister Crowley’s ‘do what thou wilt shall be the whole of the law’ and even nearer to the Wiccan adaptation thereof: ‘An it harm none, do what thou wilt.’ [….] In Lost Girls, bisexuality of some degree is the norm among men and women: in accordance to the magical law, it must be for anyone capable of desiring members of both sexes. (Eklund, 2007: n. pag.)

The jouissance of the three characters in Lost Girls thus gives way to the ominous scenes of soldiery cutting across Europe during the First World War. In juxtaposing the war’s evolving trench-lines with the flowerings of Dorothy, Alice and Wendy’s sexual awakening, Moore and Gebbie’s narrative unfolds with apparent inevitability into the bloody blossoms of men dying by the millions in fields ploughed into mud by explosives.

I’d like to turn now to The Mirror of Love as a necessary pre-text for reading Lost Girls. The epic poem was originally conceived to defy the Thatcherite legislature against the so-called “promotion” of homosexuality: the infamous Section 28 of the Local Government Act 1988 (see also the BBC Archive). Moore’s response to the enactment of this legislation was to form a publishing company called Mad Love with his then wife Phyllis and their mutual lover, Deborah Delano, in order to publish the AARGH! (Artists Against Rampant Government Homophobia!) Anthology (1988), which gained support from a diverse range of illustrators and writers opposed to political censorship and the proscription of sexuality. Moore’s own contribution was a song in praise of homosexual and homosocial culture throughout history from the images of Sappho and Spartan battle brothers to the Templars and onward through the renaissance, to the (then) current (1980s) British political landscape.

AARGH! Anthology (1988) lashed out at political censorship

[Image by Simon Zino under a CC BY-2.0 license]

In The Mirror of Love, Moore describes a world of sexuality-as-enjoyment, from the primordial to the modern and from the “animal kingdom” to the hosts of human societies. His invocation of “Blind desire” as the motor of evolution as “life’s glorious engine” presents primordiality as joyous sexuality “churning in the mud” (Moore 2004: 2), this foreshadows his conclusions in Promethea and Lost Girls that the most important forms of contact for all species are the most immediate affirmations of life. From the moment of making explicit the connection between sex and evolution, the remainder of The Mirror of Love is haunted by the spectre of death and the delegitimisation of memory, in an enforced mode of forgetting.

Moore is effectively writing a speculative utopian history, drawing together already marginal threads into narrative continuity; a unified field he had been unable to find in the history books he consulted in the writing of the piece. In the manner of those he is opposing, Moore uses the “law” of “nature” as a first reference point:

On land,

the first societies,

great herds of she-beasts,

raised their young together,

without males

[….]

The women licked

and groomed each other

with men watching,

circling, circling round (Moore 2004: 4)

Refusing the simplistic division between “nature” and “society,” Moore’s genesis, his beginning, is “three million years of motherhood” where gender distinctions are rendered immaterial beside familial affection (Moore 2004: 4). Moore follows Foucault’s (1998) analysis of the Greco-Roman ethics of homosexual/homosocial relations, seeing an anxious regulation guarding certain paranoias about power within sexual relations. Moore is thus presenting historicised thumbnail sketches of problematic sexual regulation without ideal or idyll as a long, irregular history where sex is a consistently political and politicised problem. Hence, the Spartans’ soldierly love is presented as an idiosyncrasy, but nevertheless an effectively destructive one. Moore’s blank ironic tone in the verse of The Mirror of Love suggests that this may be a deliberate removal of homosexuality to a plane on which it can be scapegoated by the rest of society. Thus, by enforcing its practice only in soldiers “who’d defend// their frontline lovers // to the death” (Moore 2004: 14), homosexuality in The Mirror of Love also foreshadows the later verses on twentieth-century violence against LGBTQ people.

Moore focuses on the resistance to such attitudes linking it to the growth of cities and civilizations where “Dignity marched // abreast with shame” (Moore 2004: 52) and love survived even in “reeking lavatories” (Moore 2004: 52). He draws onward to the upheavals of the First World War and the central warning of The Mirror of Love: against creating more of that “loam where // fascist flowers // thrived horribly” (Moore 2004: 56). In José Villarubia’s edition the verse describing the whispered rumours of “The showers” (Moore 2004: 58) faces a completely black photograph. The idea of lost hope resonates precisely with the story of Valerie in V for Vendetta (1988-9) in a horribly precise and apposite echo of George Orwell’s 1984 (1949). The page following this all-effacing blackness stands opposite a photograph of a young man raising a flame in darkness, and reads:

Darling, do not weep.

‘Twas just a dream,

a nightmare gathered on the century’s brow,

and if it comes again

I’ll hold you tight ‘til dawn,

as well I know how. (Moore 2004: 60)

Having plumbed the horror of destruction, the poem reaches out again for human-to-human communication, which is exactly what Moore continues to examine, with Gebbie, in the significantly larger project of Lost Girls. Moore extends his assertion of the value of communication using a pornographic graphic narrative because he asserts it is something that can bridge the gap between the tender and the sordid in representation; which is arguably the space where examinations of sexuality must go because expressions of sexuality do manifest in the greys and browns of deprivation as well as more colourful, enlivening shades. Moore and Gebbie are offering Lost Girls as an affirmation of the complexity of a genre regarded as mythically simple, reducible, to paraphrase Carter in The Sadeian Woman, to binaries of ones and zeroes, of male and female sex organs. If it is seen as a fantasy genre – like others they have worked on in “mainstream” comic books and underground comix – Lost Girls becomes something that can be repurposed to multifarious uses of varying sophistication; it can be seen as something potentially communicative and responsive. There is always more to be said, and Lost Girls remains controversial for other reasons unexplored here, but as a piece of speculative fiction written within an underground comix perspective on the representation of sex and sexuality it has a logical continuity with Moore’s other assertions that Art should be understood as an intervention between people.

Whatever else we need from our underground comix, we need them to test our verbal and visual capacities to respond critically to the “overground,” the dominant culture, and to affirm difference, divergence, and dissent as an affirmation of life and human contact.

CITATION: Mark P. Williams, “Speculative Resistance in Lost Girls.” Alluvium, Vol. 6, No. 1 (2017): n. pag. Web. 15 March 2017, https://doi.org/10.7766/alluvium.v6.1.05.

[author] [author_image timthumb=’on’]https://www.alluvium-journal.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/12/mark_p_williams-author-image.jpg[/author_image] [author_info]Dr Mark P. Williams is currently a Teaching Fellow at Johannes Gutenberg-Universität Mainz, Germany, where he has worked since 2014. He previously taught at the University of East Anglia (UK) and Victoria University of Wellington (Aotearoa New Zealand), and has also been a political reporter for Scoop Independent Media in the NZ Parliamentary Press Gallery. His PhD, Radical Fantasy: A Study of Left Radical Politics in the Fantasy Writing of Michael Moorcock, Angela Carter, Alan Moore, Grant Morrison and China Miéville, was awarded from the University of East Anglia.[/author_info] [/author]

Works Cited:

Carter, Angela. The Sadeian Woman: An Exercise in Cultural History. London: Virago Press, 1979.

Collins, Meredith. “History, Pornography, and Lost Girls.” ImageTexT: Interdisciplinary Comics Studies, 3(3) (2007). Web. Available at: http://www.english.ufl.edu/imagetext/archives/v3_3/lost_girls/collins.shtml (Last accessed 6 March 2017).

Eklund, Chris. “A Magical Realism of the Fuck.” ImageTexT: Interdisciplinary Comics Studies, 3(3) (2007). Web. Available at: http://www.english.ufl.edu/imagetext/archives/v3_3/lost_girls/eklund.shtml (Last accessed 14 March 2008).

Foucault, Michel. The History of Sexuality, Vol.1: The Will to Knowledge, trans. Robert Hurley. London: Penguin, 1998.

Gravett, Paul. “Alan Moore: The ‘Lost’ Interview,” Author’s website, 13 January 2008: http://www.paulgravett.com/articles/article/alan_moore1 (Last accessed 6 March 2017).

Hills, Matt. “Counter Fictions in the Work of Kim Newman: Rewriting Gothic SF as ‘Alternate-Story Stories’.” Science Fiction Studies, 30(3) (2003): 436 – 55.

Moore, Alan. The Mirror of Love, illus. José Villarrubia. Portland, OR: Top Shelf Productions, 2004.

Moore, Alan and Gebbie, Melinda. Lost Girls. Portland, OR: Top Shelf Productions, 2006.

Please feel free to comment on this article.