Iain Robert Smith

As the centrepiece of their Christmas 2015 schedule, BBC One screened an adaptation of Agatha Christie’s And Then There Were None. Scripted by Sarah Phelps and featuring a star-studded cast including Aiden Turner, Charles Dance, and Sam Neill, the adaptation was criticised in advance for deviating from its source material by “featuring drug abuse, gruesome violence and swearing” (Hastings 2015: n. pag.). After it was shown, however, critics focused less on the various minor alterations than on the remarkable level of fidelity to Christie’s work. Tim Martin in The Telegraph, for example, celebrated the mini-series for finally doing “justice to Christie’s lightless universe” (Martin 2015: n. pag.) by sticking to the original nihilistic ending of the novel rather than adopting the more upbeat ending from the stage version. Indeed, the success of And Then There Were None with audiences and critics subsequently led the BBC to commission seven new adaptations of Agatha Christie’s work and the director of BBC Content Charlotte Moore announced that their “combined creative ambition [was] to reinvent Christie’s novels for a modern audience” (Barraclough 2016).

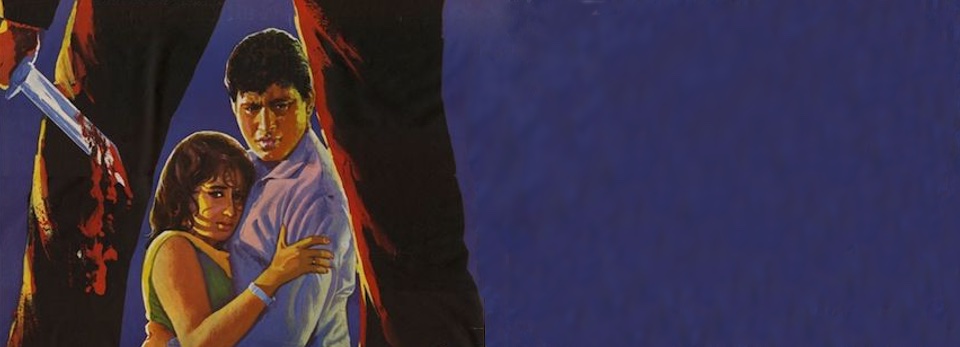

Gumnaam (1965) reminds us that there is much scholarly work to be done in studying adaptations of Agatha Christie’s novels beyond English-language adaptations produced in the UK and USA

[Images used under fair dealings provisions]

Of course, there have already been innumerable attempts to reinvent Christie’s novels for different audiences and this issue is at the centre of Mark Aldridge’s recent monograph Agatha Christie on Screen – the most comprehensive and thoroughly researched account to date of Agatha Christie adaptations. Covering everything from The Passing of Mr. Quin in 1928 through to And Then There Were None in 2015, Aldridge’s book draws on extensive archival research in order to provide an authoritative history of this phenomenon. The predominant emphasis is on English-language adaptations although Aldridge recognises the problem that most adaptations “produced outside of the UK and USA tend to be either ignored, or treated as little more than footnotes” (Aldridge 2016: n. pag.), so he attempts to cover some of the non-English language adaptations in his section on ‘International Adaptations’. As Aldridge himself admits, however, he “cannot fully redress the balance in their favour” (Aldridge 2016) and is only able to offer a brief discussion of these non-English language adaptations. Given that Christie’s work has famously sold over two billion copies worldwide, half of them in translation (Makinen 2010: 416), and has inspired adaptations in contexts as diverse as Russia, Japan, India and Germany, it is clear that there is more work to be done on the transnational adaptations of Christie’s work. In this article, therefore, I would like to focus attention on the 1965 Hindi-language adaptation of And Then There Were None. By analysing the various ways in which Gumnaam (English translation: Unknown or Anonymous)[1] adapts Christie’s novel in the Indian context, this article will investigate the cultural politics raised by this particular film, and by processes of cross-cultural adaptation more generally.

Ten Little Indians in India

Directed by Raja Nawathe, Gumnaam is perhaps best known in the West for its song and dance sequence ‘Jaan Pehechan Ho’ in which Laxmi Chhaya is accompanied by the rock and roll group Ted Lyons and His Cubs. As David Novak has discussed, the song “circulated within and helped constitute ‘alternative’ America in the 1990s” (Novak 2010: 48) with the sequence being played by The Cramps singer Lux Interior on Los Angeles TV show Request Video in the early 1990s, subsequently circulating widely on bootleg videotapes and inspiring a controversial cover version by San Francisco rock band Heavenly Ten Stems, and eventually appearing in the opening sequence of American indie film Ghost World (2001).

The song and dance sequence “Jaan Pehechan Ho” from Gumnaam has enjoyed a rich variety of afterlives in American popular culture

However, while the sequence has had a remarkably wide circulation in the West, the film itself has had much less attention in English-language fandom and scholarship. As Novak notes, the “growing North American reception of Bollywood is not necessarily based on the films themselves but on excerpts from classic Bollywood films” (Novak 2010: 40) and Gumnaam is one of the prime examples of this phenomenon. It is important, therefore, that we turn our attention to the film itself. Promoted in its trailer as “India’s First Suspense Thriller,” and promising its audience “a chill down the spine as you clutch the edge of your seats,” Gumnaam was an attempt to introduce a largely unfamiliar genre into Indian cinema. Following the plot structure of And Then There Were None relatively closely, it focuses on ten characters who are trapped on a deserted island and are bumped off one by one. Indeed, the majority of changes that are made reflect Tejaswini Ganti’s observation that the three predominant ways in which Indian filmmakers adapt plotlines from imported films are by “adding ‘emotions,’ expanding the narrative, and inserting songs” (Ganti 2004: 77). Although the film retains much of the basic plot structure, it adds dream sequences in order to visualise its characters’ emotional states, it expands the narrative with additional motivation for the killer, and it incorporates numerous song and dance sequences throughout.

The expansions of the narrative are particularly significant. While there has been something of a critical reappraisal of Christie’s work in recent years, it is true that “for the majority of the twentieth century the critical consensus has been that her plotting was her major claim to fame” (Makinen 2010: 416) and that her writing style and characterization has been less acclaimed. Indeed, in one of the first critical studies of Christie’s oeuvre, Robert Barnard argues that “her scene-painting and characterization are marked by generality rather than vividness” (Barnard 1980: 123) and that it is precisely this perceived weakness that gives her work a ‘universal’ appeal. In other words, to explain Christie’s worldwide appeal, Barnard argues that “her books are like a child’s colouring-book, where the basic shape of the picture is provided, and the child fills in the details and decides on the colours himself” (Barnard 1980: 123). While this a rather back-handed compliment, it may explain to some extent why Christie’s work has proven to be so eminently adaptable – that it is the tight plotting that is their primary appeal rather than the writing style, English locations and characterisation.

A “beautifully bizarre go-go soundtrack”: Gumnaam’s original soundtrack, composed by Indian duo Shankar/Jaikishan, has contributed to the film’s lasting appeal

[Image used under fair dealings provisions]

The fact that Gumnaam makes some crucial changes to the plot structure of And Then There Were None, therefore, has led to criticism from viewers familiar with Christie’s novel. As Stephen Knight has argued, “Christie had the art of making the reader acknowledge, in admiring bafflement, that the final coup was the only possible outcome of her cunning plotting” (2003: 82) and it is evident that the changes to the narrative of Gumnaam create a more convoluted resolution that is less tightly structured. Many of the other changes, however, are more fruitful with the widely-acclaimed Shankar-Jaikishan soundtrack contributing distinctive songs such as “Gumnaam Hai Koi” and “Peeke Hum Tum Jo” in addition to the aforementioned “Jaan Pehechaan Ho.” The sizable number of central roles also allows for appearances from a number of renowned stars of 1960s Hindi cinema including the Elvis-lookalike Manoj Kumar as Inspector Anand, the character actor Pran as Barrister Rakesh, and the comedy-relief specialist Mehmood as the Butler.

Similar to the 1965 British adaptation Ten Little Indians, the repressed spinster character from the novel becomes the much younger and more glamorous Anglo-Indian character Kitty Kelly, played by the item-number star Helen. “Item numbers” referred to the song-and-dance sequences used in Bollywood films, which frequently had little to do with the film’s plot. Rather, these scenes offered entertaining interludes within the story with their colourful costumes, frequent changes in location, striking choreography and, of course, their star dancers. Helen became famous as an “item girl” whose seductive appeal lay in her exoticism: born in Burma and of Anglo-Indian parentage, she embodied an outré sexuality often denied her Hindi counterparts. Having secured her reputation as a highly bankable “item” performer in the early 1950s, Helen’s appearance in popular Bollywood films from the 1950s through to the 1970s lent these films a “visual seduction.” As seen in the screengrabs below, her appearance in the song “Baithe Hain Kya Uske Paas” from Jewel Thief (1967) [see bottom right image] demonstrates the exotic and frequently outlandish costumes she wore, evoking a vampish, sultry persona through the use of exaggerated eyeliner (to emphasise her South-East Asian heritage) with ostrich feathers in her hair suggestive of an Orientalist kind of decadenece (Varia 2012: 69). This explicit Orientalist framing of Helen’s stage persona as both part-Indian and also inescapably “Other” can also be seen in the 1969 film Sachchai [see the left-hand image below], which features lavish costume and set design to heighten the star’s exotic seductiveness, but also reveals Bollywood’s generalised understanding of what constitutes the exotic and the Other. As Jerry Pinto describes: “Helen was exotic as all vamps must be, but the Bombay film industry’s somewhat uncomplicated notion of exotica was such that Helen could be made to fit any set of circumstances” (Pinto 2006: 82). This vampish identity was also alluded to in a number of items in which Helen appears to be sexually predatory, drinks alcohol (sometimes to excess, as seen in the song “Piya Tu Ab To Aaja” from Caravan (1971) [see top-right image below]), smokes cigarettes and often plays a minor character who is killed off, whilst the “good” female protagonists survive to these films’ conclusions.

The H-Bomb: Burmese-born sensation Helen appeared as a dancer in more than 700 Bollywood films during her career, including Gumnaam

[Images used under fair dealings provisions]

In Gumnaam Helen performs a Western character, as Jerry Pinto recounts in his biography of Helen: “Kitty Kelly is the gold standard of the stereotype Anglo-Indian young woman” (Pinto 2006: 69), presented as overly westernized and liberated in contrast with the heroine Asha who is depicted as much more traditional. There is an obvious tension, however, between this stereotyped depiction of an overly Westernised character, and the ways in which the film itself makes use of Western influences. Beyond the use of Agatha Christie’s novel, the film adapts many other elements from Anglo-American culture including the haunting melody of the song “Gumnaam Hai Koi,” a reworking of the theme song to the 1963 Hollywood film Charade. The addition of songs, therefore, is one of the key ways in which Christie’s work has been localized for the Indian context, yet it also part of a sedimented history of borrowings back and forth that complicate any reading of Gumnaam as a straightforwardly “Indian” adaptation of Agatha Christie’s novel. We need a model that can engage with these processes of cross-cultural adaptation without falling into that kind of cultural essentialism.

And Then There Were Many

In my forthcoming book The Hollywood Meme: Transnational Adaptations in World Cinema, I propose that we can use the structuring metaphor of the “meme” in order to investigate these processes of transnational adaptation. The term describes a unit of culture that spreads, adapts and mutates in a manner roughly analogous to biological evolution, and it allows us to study the ways in which texts are adapted across national and cultural contexts. One of the reasons that I settled on this evolutionary model was because it draws our attention to the ways in which certain “memes” flourish in their new contexts whereas others fail to adapt to their new surroundings and die out.

It is therefore significant that while Gumnaam was one of the first Indian adaptations of Agatha Christie’s work, it was far from the last. In 1973, for example, B.R. Chopra directed an adaptation of Christie’s play The Unexpected Guest titled Dhund (Fog) and this subsequently inspired further adaptations of the same work in the Kannada and Tamil industries. More recently, the Miss Marple story The Mirror Crack’d from Side to Side was adapted in the Bengali film Shubho Muharat (2003) whilst The ABC Murders inspired the Malayalam film Grandmaster (2012). As this process suggests, Agatha Christie’s work has had a substantial presence across the various different regional film industries within India yet these films have rarely been addressed in scholarship. Too often the focus has been on the US and UK adaptations and this relegates non-English language adaptations such as these to little more than a footnote. As I hope to have demonstrated in this short article, therefore, we need to shift our perspective in order to properly interrogate the truly global nature of these processes of adaptation.

CITATION: Iain Robert Smith, “Bollywood Adaptations of Agatha Christie,” Alluvium, Vol. 5, No. 4 (2016): n. pag. Web. 30 October 2016, http://dx.doi.org/10.7766/alluvium.v5.4.04.

Dr Iain Robert Smith is Lecturer in Film Studies at King’s College London. He is author of The Hollywood Meme: Transnational Adaptations in World Cinema (EUP, 2016) and co-editor of the collections Transnational Film Remakes (with Constantine Verevis, EUP, 2017) and Media Across Borders (with Andrea Esser and Miguel A. Bernal Merino, Routledge, 2016). He is co-chair of the SCMS Transnational Cinemas Scholarly Interest Group and co-investigator on the AHRC-funded research network Media Across Borders.

Dr Iain Robert Smith is Lecturer in Film Studies at King’s College London. He is author of The Hollywood Meme: Transnational Adaptations in World Cinema (EUP, 2016) and co-editor of the collections Transnational Film Remakes (with Constantine Verevis, EUP, 2017) and Media Across Borders (with Andrea Esser and Miguel A. Bernal Merino, Routledge, 2016). He is co-chair of the SCMS Transnational Cinemas Scholarly Interest Group and co-investigator on the AHRC-funded research network Media Across Borders.

Notes:

[1] This title is a play on the mysterious U.N. Owen who lures the characters to the island in the original novel.

Works Cited:

Aldridge, Mark. Agatha Christie on Screen. London: Palgrave, 2016.

Barnard, Robert. A Talent to Deceive: An Appreciation of Agatha Christie. New York: Dodd Mead, 1980.

Barraclough, Leo. “BBC Greenlights Seven New Agatha Christie Adaptations.” Variety, 24 August 2016 (accessed 26 October 2016): http://variety.com/2016/tv/global/bbc-seven-new-agatha-christie-adaptations-1201843668/

Ganti, Tejaswini. Bollywood: A Guidebook to Popular Hindi Cinema. London: Routledge, 2004.

Hastings, Chris. “What HAS the BBC done to Agatha Christie?” Daily Mail, 12 December 2015 (accessed 26 October 2016): http://www.dailymail.co.uk/tvshowbiz/article-3357749/What-BBC-Agatha-Christie.html

Knight, Stephen. “The Golden Age” in Martin Priestman (ed.) The Cambridge Companion to Crime Fiction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003: 77-94.

Makinen, Merja. “Agatha Christie (1890–1976)” in Charles Rzepka and Lee Horsley (eds.) A Companion to Crime Fiction. Chichester: Wiley, 2010: 415-426.

Martin, Tim. “And Then There Were None.” The Telegraph, 28 December 2015 (accessed 26 October 2016): http://www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/tvandradio/tv-and-radio-reviews/12071655/And-Then-There-Were-None-episode-three-review.html

Novak, David. “Cosmopolitanism, Remediation, and the Ghost World of Bollywood.” Cultural Anthropology, 25:1 (2010): 40-72.

Pinto, Jerry. Helen: The Life and Times of an H-Bomb. New Delhi: Penguin Books, 2006.

Smith, Iain Robert. The Hollywood Meme: Transnational Adaptations in World Cinema. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2016.

Vaira, Kush. Bollywood: Gods, Glamour, and Gossip. New York: Columbia University Press/Wallflower, 2012.

Please feel free to comment on this article.

One Reply to “Bollywood Adaptations of Agatha Christie”