Sarah Chihaya

Faultily faultless, icily regular, splendidly null

Dead perfection, no more…[i]

When human flesh first touches synthetic flesh in the Black Mirror episode “Be Right Back” (2013), the human recoils, but keeps touching all the same: “You’re so smooth—how are you so smooth?” whispers Martha (Hayley Atwell) to the android simulacra of her dead partner, Ash (Domnhall Gleeson). The android body is framed as both supernatural and technological, more warped fairy tale than science fiction. The Ash-droid is unfazed by her perturbed fascination, recognizing his own strangeness to the rough human touch, and explains that his skin’s uncanny perfection is derived from the imperfect process of “texture mapping – the really tiny details are visual, 2-D. Here, try my fingertips.” Martha tentatively strokes his ungrained fingers with her own textured ones, again repelled but compelled. “See?” he says, “Weird. Does it bother you?” “No?” murmurs Martha, distraught but strangely desiring, “I mean yeah? I’m not sure.”

The machinery under the seamless, magical perfection of synthetic flesh.

[Image by Steve Rainwater under a CC BY licence]

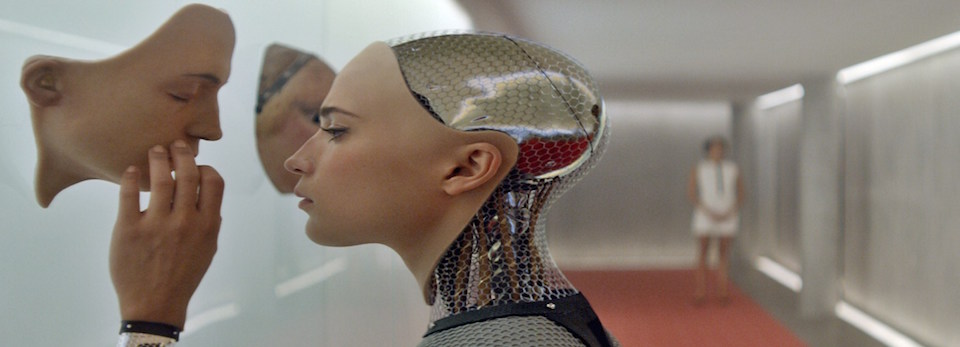

A similar convergence of horror and desire for the seamless, magical perfection of synthetic flesh generates the odd affective climax of Ex Machina (2015). The android Ava (Alicia Vikander), half clothed in skin as uncannily perfect as Ash’s, half visible machinery, discovers the deactivated, frighteningly realistic remains of earlier models in her sadistic creator’s Bluebeard-like closet of morbidly beautiful, inert female bodies. Slowly, she peels the flesh from one and adds it to her own body, covering her robotic skeleton with unmarked new skin. Her human would-be savior, Caleb (also played by Gleeson), watches from a distance, captivated and frightened, as Ava carefully completes her own body. As she smooths swaths of flesh onto her frame, they fuse together instantaneously, with an almost-inaudible zing and a faint tracery of golden light, an effect that is half sci-fi, half fairy-tale magic. In her seamless encasement, she is too perfect to be human: untextured, unreadable. And does it bother us? No. Yeah. We’re not sure.

Both “Be Right Back” and Ex Machina appear on the surface to be about our anxieties about the limitations (or lack thereof) of human-level artificial intelligence, but rather than fixating on questions of the synthetic mind, both texts actually linger disturbingly on the details of the synthetic body. Amidst contemporary anxieties about the terrifying potential of artificial super intelligence, they remind us that flesh—our own and that of others—is just as much of a human obsession as the mind. We constantly look at flesh; we touch it; we eat it; we judge it. We are it: authentic fleshiness is perhaps one of the most significant markers of what seems natural and “real” to the human senses.

As writer Charlie Brooker (Black Mirror) and writer-director Alex Garland (Ex Machina) both astutely note, fake flesh has become just as powerful an obsession—or more accurately, a fetish. This is both a fantastical fixation and a strangely quotidian one: are those real breasts? Is this real beef? Is that real skin? Does it feel, taste, smell, act like the real thing? What kind of science—or, as both Ex Machina and Black Mirror suggest coyly, occult tech magic—would it take for fake flesh to surpass the real thing? Like human-level artificial intelligence (or beyond), viable synthetic flesh is at once a utopian scientific possibility and a terrifyingly dystopian one: either way, perhaps the creation of new fleshly bodies is at once the frontier of technology, and the frontier of our most primal anxieties about the latter.

Martha distraught by and yet strangely desiring of the Ash-droid.

[Image by Channel 4 used under fair dealings provisions]

Human-level intelligence is a given assumption for Brooker’s android, Ash. Martha communicates with a version of Ash that’s generated from his traces in social media and personal messages, first by instant message, then on the phone; as the friend who signs her up for the service comments, he was “a heavy user,” who left something akin to full version of himself floating in the cloud. Cloud-Ash “sounds just like” human-Ash and, as he asserts time and again, he is him. In fact, he is at once more and less than human-Ash; cloud-Ash assimilates information instantaneously, constantly picking up missing, personal tics and cues from Martha to add to his repertoire, while also searching data external to human-Ash’s traces—a kind of advanced Siri, whose ability to learn and bank of knowledge is more replete than any human brain could possibly be. Martha accepts this aspect of cloud-Ash with an ease that is initially surprising—but once we examine our own day-to-day interactions with the AI we already have at hand, perhaps not so surprising.

Clearly, the question of Ava’s and Ash’s android natures extends beyond the issue of pure artificial intelligence, as framed by Katherine Hayles’s observation that in the Turing test, “the erasure of embodiment is performed so that ‘intelligence’ becomes a property of the formal manipulation of symbols rather than enaction in the human lifeworld” (Hayles xi). It is in fact the very idea of convincingly embodied “enaction in the human lifeworld” that both of these non-human beings confront: it is the housing of the post-Turing artificial intelligence in convincing, better-than-human synthetic bodies that both “Be Right Back” and Ex Machina interrogate with unease. The synthetic bodies in Black Mirror and Ex Machina are at once utterly individual and utterly indeterminate. They are at once totally, intimately unique—Ash’s is a well-beloved, much-desired face, while Ava’s face is custom designed to match Caleb’s preferences in pornography. Upon arrival, cloud-Ash’s body is nothing but an eerily blank body-form, a mass of pure, unfeatured biological substrate, vacuum packed in plastic like grocery store chicken, while Ava, as we have seen, rebuilds and reshapes herself from the interchangeable components of other synthetic bodies. This is what makes them simultaneously repellent and irresistible to both Martha and Caleb: Ash and Ava are individually crafted, bespoke bodies.

Android Ava touching fake skin.

[Image from ‘Ex Machina’ used under fair dealings provisions]

The human bodies we see in both “Be Right Back” and Ex Machina are depicted as increasingly fallible, damaged, and even, at times, repulsive. Martha, pregnant, is debilitated by fits of vomiting and nausea; Nathan blacks out drunk and wakes up hungover, and requires constant upkeep with juice cleanses and exercise regimes. Most notably, Caleb grows more and more exhausted and maddened by his interaction with both Ava and her creator, an exhaustion that culminates in his increasing confusion about whose bodies are really human: in a dramatic confrontation with his own physicality, he slices an arm open with a razor blade, uncertain if he will find flesh and blood or wires and gears inside. Caleb’s confusion offers an intriguing mirror for the viewer’s own confusion, watching both films back to back. The paired casting of Domnhall Gleeson as android in one and human in the other, though apparently by chance, makes “Be Right Back” and Ex Machina productively eerie textual doppelgängers for each other, wherein Gleeson’s own body serves as an uncanny reminder that we must constantly ask whose flesh is or isn’t real. Garland plays up this confusion throughout Ex Machina, initially bathing Caleb in light that renders his fair skin as seemingly luminous and flawless as Ava’s own, and gradually shooting him in more and more textural detail until, in the near-suicide episode, he grimly peers into his own body’s workings with bloodshot, dark-circled eyes: weary, failing, human eyes. In revealing the unbreachable gap between perfectible fake flesh, and irreversibly destructible human flesh, both “Be Right Back” and Ex Machina suggest that we must reevaluate the kinds of narratives we tell ourselves about the limitations of non-human bodies and minds (specifically the comforting bedtime story that they will always be somehow limited)—and in turn, reconceive of how they might, in turn, look at us.

For it is not only the fear of these uncanny, quasi-magical superior minds and bodies that makes these new synthetic beings so alarming. What is perhaps most disconcerting about Brooker and Garland’s twenty-first century android fictions is their exposure of the strangest fairy tale of all: the very idea that they would want to be human. What “Be Right Back” and Ex Machina both emphasize is the foreign idea that the android might be indifferent to us. The sentimental view of the android limited by self-restricting, fairy tale aspirations to humanity is firmly debunked in by both Brooker and Garland in different ways. We cannot know what their new androids want, and that is what makes them so alarming: if “Pinocchio” is no longer the script for android Bildung, then what is? Interestingly, Ash is rendered simultaneously both more and less menacing by an utter lack of desire (another mark of his radical inhumanity). Though he goes through the motions of being Martha’s companion, he expresses no wishes or needs, unless told that human-Ash would do so—while the only thing that keeps him from being a threat is this complete, uncanny void of want, it is also what makes him so alarming. Ava, on the other hand, seems desperately to want—but we don’t, and can’t, know what. And in fact, this is Ex Machina’s most frightening suggestion: that we can never know what androids dream of. Certainly not electric sheep, and now, certainly not of human life.

Though she focuses on the “vital materiality” of things rather than androids, the fetishistic fallacy of the human fantasy that these figures of alien non-humanity should relate at all to us or our desires is neatly summed up by Jane Bennett in her introduction to Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things (2010):

Though the movements and effectivity of stem cells, electricity, food, trash, and metals are crucial to political life (and human life per se), almost as soon as they appear in public (often at first by disrupting human projects or expectations), these activities and powers are represented as human mood, action, meaning, agenda, or ideology. This quick substitution sustains the fantasy that “we” are really in charge of all those “its”—its that, according to the tradition of (nonmechanistic, nonteleological) materialism… reveal themselves to be potentially forceful agents. (Bennett x)

Haraway emphasizes the radical and unknowable otherness of non-human desire.

[Image by PhOtOnQuAnTiQuE under a CC BY NC ND licence]

This turn towards the unknowable agency of the “its” also recalls Donna Haraway’s earlier, radical theorization of the cyborg, so glibly ignored by narratives of the Pinocchio-style android. Haraway also clearly emphasizes the radical and unknowable otherness of non-human desire: “The cyborg does not dream of community on the model of the organic family, this time without the Oedipal project. The cyborg would not recognize the Garden of Eden; it is not made of mud and cannot dream of returning to dust” (Haraway 9). Yet, unlike the forward-speculating claim in Haraway’s manifesto that, in our contemporary world, “we are cyborgs,” “Be Right Back” and Ex Machina suggest chillingly that we have already accelerated past any possible point of real convergence with the artificial mind or the synthetic body. We humans may still be cyborgs, “creatures simultaneously animal and machine, who populate worlds ambiguously natural and crafted,” but perhaps our hybrid world has already receded into an irrecuperable past behind the wholly synthetic android future-dwellers of Brooker’s and Garland’s fictions (Haraway 8). For, unlimited by biological restrictions, they can continue living their alien lives, regardless of what happens in the world: passive and undesiring Ash waits, perfect and unaging, for the future to happen, locked in the hidden space of Martha’s attic like the bodies in Bluebeard’s chamber (or Nathan’s closet). Ava, active and full of unknowable desire, steps out into the world, after restoring herself fully to vibrantly non-human bodily life. In the end, it is the human body itself that becomes Bluebeard’s bloody chamber: at the close of Ex Machina, it’s Caleb who’s entombed, locked by Ava in the prison of Nathan’s fortress, and in the prison of his fallible human flesh.

Perhaps the real contemporary anxiety about the android body that lies at the heart of “Be Right Back” and Ex Machina is that these better, more replete bodies and minds are more suited than our feeble, unsustainable ones to survive a changing planet, and that the Earth itself, indifferent to this changing of the guard, is already no longer our world—it is theirs to inhabit, theirs to experience. This possibility is flagged by Caleb’s repeated visions of Ava stepping out into a sunlit forest for the first time, then by the Ex Machina’s final shot of her stepping out into the sensory overload of the city. What does it feel like to her—that first touch of wind or rain or sun on unmarked, untextured synthetic skin?

Weird. Does it bother her?

No. Yes. We cannot know.

CITATION: Sarah Chihaya, “Fake Flesh: Black Mirror and Ex Machina,” Alluvium, Vol. 4, No. 5 (2015): n. pag. Web. 30 October 2015, http://dx.doi.org/10.7766/alluvium.v4.5.02

Dr Sarah Chihaya is an assistant professor in the Department of English at Princeton University, where she specializes in contemporary fiction and film, and is currently at work on her first book, The Unseen World: Metanarrative and Forms of Contemporary Fiction. Her writing has recently appeared in Public Books, Modern Fiction Studies, and C21 Literature: 21st Century Writings, and she is the editor of Contemporaries at Post45 (http://post45.research.yale.edu/sections/contemporaries/). She received her PhD in Comparative Literature from the University of California, Berkeley.

Dr Sarah Chihaya is an assistant professor in the Department of English at Princeton University, where she specializes in contemporary fiction and film, and is currently at work on her first book, The Unseen World: Metanarrative and Forms of Contemporary Fiction. Her writing has recently appeared in Public Books, Modern Fiction Studies, and C21 Literature: 21st Century Writings, and she is the editor of Contemporaries at Post45 (http://post45.research.yale.edu/sections/contemporaries/). She received her PhD in Comparative Literature from the University of California, Berkeley.

Website: https://english.princeton.edu/people/sarah-chihaya

Twitter: @so_jane_lane

Notes:

[i] Alfred, Lord Tennyson, “Maud: A Monodrama” (1855).

Works Cited:

Black Mirror, “Be Right Back” (series 2, episode 1). Dir. Owen Harris, writ. Charlie Brooker. Perf. Hayley Atwell and Domnhall Gleeson. Zeppotron/Channel 4, 2013. Television.

Haraway, Donna. “A Manifesto for Cyborgs: Science, Technology, and Socialist Feminism in the 1980s,” in The Haraway Reader. New York: Routledge, 2004. Print.

Hayles, Katherine. How We Became Posthuman: Virtual Bodies in Cybernetics, Literature, and Informatics. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1999. Print.

Ex Machina. Dir. Alex Garland. Perf. Alicia Vikander, Domnhall Gleeson, and Oscar Isaac. DNA Films, 2015. Film.

Mannoni, Octave. Je sais bien, mais quand même… Clefs pour l’imaginaire ou l’autre scène. Paris: Éditions de Seuil, 1969, 9-33. Print.

Grimm, Jacob and Wilhelm. “Fitcher’s Bird.” In The Classic Fairy Tales: A Norton Critical Edition, ed. Maria Tatar. New York: W.W. Norton and Company, 1999. Print.