Matthew Griffiths

Our climate crisis is constitutively complicated, because rather than dividing culprits from innocents, it both implicates us and impacts on us, to greater or lesser extents. Bronislaw Szerszynski observes in his article ‘The Post-Ecologist Condition: Irony as Symptom and Cure’ (2007) that it entails a kind of irony in which ‘there are no separate groups of perpetrators and victims’ (348). If we are environmentally oriented readers of literature – ecocritics – our response to this situation should account for the fact that at some point ‘Irony became not just rhetorical form but philosophical content’, as Szerszynski maintains (348; author’s italics).

Obviously, this has implications for far more than literary form, but it does entail particular problems for the discourse of climate change. That in turn affects public engagement with the issue – or indeed, lack of engagement. The ironic context identified by Szerszynski undoes the ease with which we can readily accept a narratorial authority, because personal experience is at odds with an awareness of global change. However, the authoritative, narratorial self remains a dominant motif in environmental writing, positioning itself outside the problem in a way that Szerszynski maintains is now untenable: ‘the ironist as an outside observer of the irony, on the moral high ground looking down,’ is ‘a positing of the ethical actor [that] seems inadequate for an age … in which even social movements get caught up in this logic’ (347–8).

Problems for the nature writing tradition: the irony of climate change discourse is that it does not distinguish between victims and perpetrators

[Image by Martha de Jong-Lantink under a CC BY-NC-ND license]

In this article, I’m going to examine two pieces, whose responses to climate change reveal, respectively, the problems of treating it in terms of the nature writing tradition, and the textual scope, complexity and paradoxes it can in contrast be used to provoke. The first of these, Paul Kingsnorth’s Orion Magazine piece ‘Confessions of a Recovering Environmentalist’ (2012), uses an autobiographical mode, and in attempting to assert an authoritative position on environmental change he simultaneously undermines his argument. In this account of his formative experiences of environmentalism and his increasing dissatisfaction with that movement – in particular its advocacy of renewable energy – Kingsnorth demonstrates a powerful and persuasive attachment to a version of nature comprising ‘wild places and the other-than-human world’.

He is aware of the cultural mediation of this vision, inasmuch as he discusses the colonial practice of ‘forcing tribal people from their ancestral lands, which had been newly designated as national parks, for example, in order to create a fictional “untouched nature”’. However, he only employs this critique in relation to historically and geographically remote contexts, and is not prepared, reflexively, to examine how his own argument is based on such a fiction. He celebrates ‘The mountains and moors, the wild uplands’ of Britain; but in the critical context he offers for colonial practice, these landscapes too must come under question. Given the extent of prehistoric forestation in Britain, how can we legitimately claim the moor and uplands are not, too, the product of human clearances? In A Cultural History of Climate (2010), Wolfgang Behringer points out that ‘In the Holocene Homo sapiens sapiens began to make massive incursions into nature, turning it into a cultural landscape’ (39), so, in seeking to escape culture by turning to his ‘uplands’, Kingsnorth actually stumbles into a landscape that was always already culturally created.

He therefore indulges in something that ecocritic Lawrence Buell recognises in our experience of place, our capacity ‘to fantasize that a pristine-looking landscape seen for the first time is so in fact’ (Writing for an Endangered World, 68). Kingsnorth’s sniffy remark that ‘Most of us wouldn’t even know where to find’ the wild world is thus problematic. He supposes that the wild world is uncomplicatedly there but that most of us cannot be bothered to find it. However, his slight has another reading in the context of Szerszynski’s state of general irony: we can’t locate the wild world not because we are ignorant or lazy, but because it never existed as Kingsnorth imagines it, free of human mediation.

Wild nature: Paul Kingsnorth interrogates his own attachment to a vision of nature as untouched and other-than-human

[Image by Ray Bouknight under a CC BY license]

He demonstrates similarly problematic doublethink about the agendas we bring to climate change. He rightly critiques the notion of sustainability as being informed by ‘the expansive, colonizing, progressive human narrative’ – the same ‘confident belief in the human ability to control Nature’ that Mike Hulme characterises as ‘constructing Babel’ in Why We Disagree About Climate Change (351, 348). However, Kingsnorth is unable to use such critiques reflexively and examine the irony of his absolutist position. He cites the arguments of his environmentalist friends – ‘Didn’t I know that climate change would do far more damage to upland landscapes than turbines?’ – but rather than offer a reasoned answer, his strategy is to mock his opponents by adopting their jargon: ‘Their talk was of parts per million of carbon, peer-reviewed papers, sustainable technologies, renewable supergrids, green growth, and the fifteenth conference of the parties’. Kingsnorth does not consider that for all this rhetoric of sustainability, it has had little effect on the actual state of the climate.[1] Instead, he emotes against the unpleasant presence of renewable energy technology in his immediate environment: ‘The mountains and moors, the wild uplands, are to be staked out like vampires in the sun, their chests pierced with rows of five-hundred-foot wind turbines and associated access roads, masts, pylons, and wires’.

Claiming a ‘frustrated detachment’ from conventional politics, Kingsnorth strives to place himself in the now impossible position of ‘the ironist as an outside observer of the irony, on the moral high ground looking down,’ in Szerszynski’s words. But ‘frustration’ bespeaks an engagement with politics at the same time as ‘detachment’ disavows it. In the absence of a reflexively critical quality, Kingsnorth cannot mount a cogent argument against the politics of ‘sustainability’; instead the titular ‘Confessions’ governs the tone and mode of the piece. ‘It took a while before I started to notice what was happening,’ Kingsnorth writes, ‘but when I did it was all around me. The ecocentrism—in simple language, the love of place, the humility, the sense of belonging, the feelings—was absent from most of the “environmentalist” talk I heard around me’ (author’s italics). The snobbery tacit in the earlier remark about ‘not knowing where to find’ the wild recurs in Kingsnorth’s denouncement of ‘environmentalists with no attachment to any actual environment’, as though an informed commitment to the planet as a whole could always be trumped by topophilia.

In order to re-affirm the value of wild nature, Kingsnorth has to create a technologist vision of environmentalism as its opposite, but he refuses to, or cannot, answer its case. This rhetorical strategy means he is forever turning away, leaving him with nowhere else to go than the notion of nature to which he clings at the last. ‘I am leaving on a pilgrimage to find what I left behind in the jungles and by the cold campfires and in the parts of my head and my heart that I have been skirting around because I have been busy fragmenting the world in order to save it; busy believing it is mine to save’. Despite his acknowledgement of the falsity of one conception of nature – that it is to be ‘saved’ by human beings – Kingsnorth still persists with a faith in unalterable nature, with the question raised by climate change’s effect on the entire landscape unanswered, hanging ominously over that landscape. The figure of the Romantic exceptionalist, always turning away from the crowd, is poorly matched to the problem, and Kingsnorth’s metaphorical retreat into a nature that isn’t what he imagines it to be is a retreat into solipsism.

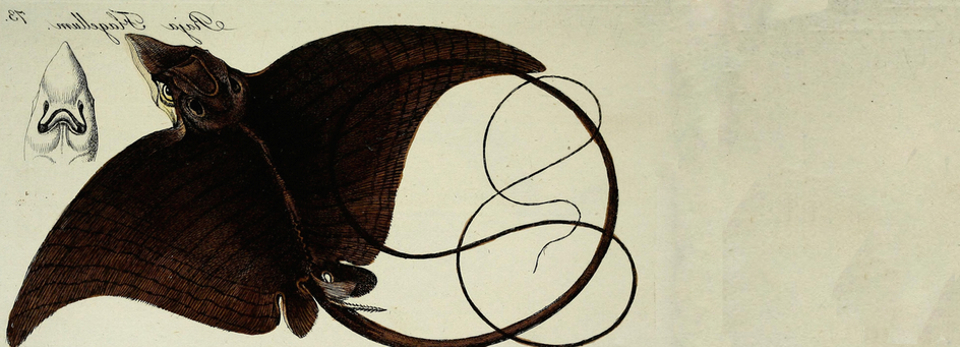

Facing up to the challenges of a dwindling biodiversity requires more than mere topophilia, and necessitates a variety of rhetorical forms and strategies

[Image by Biodiversity Heritage Library under a CC BY license]

In contrast, writing that eschews a particular genre, that is not straightforwardly critical or creative, fictional or nonfictional, gives itself the opportunity to rethink rather than reinforce conventional reader–writer relations. Sheila Nickerson’s ‘Earth on Fire’, from Interdisciplinary Studies in Literature and the Environment 5.1 (1998), comprises a broader mixture of tones and modes than Kingsnorth’s polemical ‘Confessions’. The essay opens with the combative assertion that ‘The debate on global warming is no longer a debate’ (67), but Nickerson then moves associatively through reports of crimes against women, nuclear proliferation, deforestation, disease epidemics, authorial anecdotes and poetic speculation, which across her 20 pages stack up paratactically to implicate a common cause. Her section on Venus, for instance, traces the planet’s mythical and astronomical associations, before suggesting ‘We are drawn to her, Earth’s sibling, but she is only a cauldron, and perhaps a beacon: a family portrait of what we might become with age, an inferno trapped by carbon dioxide’ (73). In this sentence, Nickerson’s prose transgresses categories such as science, folklore and current affairs to show how all are invoked by the notion of an ‘Earth on Fire’.

Sometimes, certainly, Nickerson reads as polemical herself – ‘we are strangling earth’ – and other times the poetry runs away with her and she is plain unscientific – ‘the galaxies within our universe reach out and the universes beyond our universe’ (85, 82). With the pull of different tones, however, Nickerson avoids the problematic assertion of personal authority that Kingsnorth attempts. Instead, she offers a disorienting and abrupt sweep of opinion:

Some say the heating of the oceans will lead to greater evaporation and snowfall, precipitating a new ice age; the heavy snowfall on Mount Washington in the spring of 1997, they say, is clear proof. Some say the 11,500 year cycle is up; the poles are shifting. The enormous increase in tornadoes and freakish winds is a sign. Some cite the calendar of the ancient Mayans and say their study of sunspots and solar magnetism clearly points to global catastrophe (68).

This offers a concise yet powerful example of the diversity of discourses attached to climate change – meteorological, geological and mythological – that Hulme analyses in Why We Disagree About Climate Change, able to see it from various perspectives and at different scales. For Kingsnorth, on the other hand, ‘climate change’ is merely an excuse for human business as usual, consisting in a particular strain of easily satirised political rhetoric.

The Portage Glacier has confounded glaciologists by the speed and scale of its retreat

[Image by wehardy under a CC BY-NC-ND license]

‘Earth on Fire’ also demonstrates the difficulties of assuming the nature we experience offers a stable truth. The wilderness into which Kingsnorth rhetorically retreats is shown by climate change to be profoundly contingent: ‘the famous Portage Glacier is in catastrophic retreat,’ Nickerson writes, ‘a stage glaciologists had not expected it to reach for another twenty years. Once Alaska’s most visited site, it now cannot be seen from the visitor center built in 1979 for optimal viewing’ (67). If the forces of nature do not conform to lay experience, they can nevertheless be managed to construct a simulacrum of “nature”; Nickerson here taking up a question that Kingsnorth evades. She explains that clearcuts – a process in which ‘hillsides [are] stripped and wood fires burned’ –

for the most part, are made off the route of the cruise ships that bring half a million tourists to Southeast Alaska each summer. Those tourists, full of dreams of the last American wilderness, travel the Inside Passage only a hillside away from revelation. Carefully protected, they go home for the most part with their dreams intact (81).

Nickerson is alive here to the potency of our ‘dreams’ of nature, where Kingsnorth in his nostalgia unconsciously succumbs to them. Her sensitivity to these differences means she is able to distinguish actual from supposed change: ‘It is not just a question of fireflies remembered with nostalgia from childhood […] Life forms are disappearing rapidly, along with their ecosystems’ (74). Even when she adopts a localist strategy – ‘Every time I go to look at the Mendenhall Glacier near my home in Juneau, I am amazed to see how far it has retreated since I moved into its neighborhood a quarter of a century ago’ (67) – it is nevertheless set in the essay’s global context. These personal experiences take their place amid the abrupt associations and disjunctions of the essay as a whole, which formally fail to reconcile – indeed, choose to resist reconciliation between – the essay’s differing scales.

Modes of writing premised on integrity, reconciliation and the harmony of nature are not suited to articulating and negotiating the cultural complexities of climate change. Where Kingsnorth’s response is ultimately satisfied with the turn into imagined wilderness rather than a confrontation with the problem, he is indicative of proto-Romantic readings of climate change. In contrast, Nickerson’s essay shows the potential for more fragmentary, abrupt and associative writing that does not seek to shore up nostalgic visions of nature, nor forgo the chance to see nature’s complexities and its extensive implications for the state and future of our planet.

CITATION: Matthew Griffiths, “Changing the Climate of Writing,” Alluvium, Vol. 3, No. 1 (2014): n. pag. Web. 24 September 2014 http://dx.doi.org/10.7766/alluvium.v3.1.03.

Dr Matthew Griffiths recently completed his PhD in English Studies at Durham University under Professor Timothy Clark and Dr Jason Harding. His novel The Weather on Versimmon explores ecological themes in a science-fiction setting, and his debut poetry pamphlet, How to be Late, was published by Red Squirrel in 2013.

Dr Matthew Griffiths recently completed his PhD in English Studies at Durham University under Professor Timothy Clark and Dr Jason Harding. His novel The Weather on Versimmon explores ecological themes in a science-fiction setting, and his debut poetry pamphlet, How to be Late, was published by Red Squirrel in 2013.

Notes:

[1] Certainly not compared to, say, the effect of the post-2007 recession on carbon emissions; the UK’s independent Committee on Climate Change, for instance, reports that ‘greenhouse gas emissions fell 8.6% from 2008 to 2009 with reductions of 9.7% in CO2 and 1.9% in non-CO2 emissions. But the reduction was largely due to the recession and other exogenous factors’ (Meeting Carbon Budgets 3).

Works Cited:

Behringer, Wolfgang. A Cultural History of Climate, trans. Patrick Camiller (Cambridge: Polity, 2010).

Buell, Lawrence. Writing for an Endangered World: Literature, Culture, and Environment in the U.S. and Beyond (Cambridge, MA: Belknap-Harvard University Press, 2001).

Committee on Climate Change. Executive Summary. Meeting Carbon Budgets – Ensuring a Low-Carbon Recovery: 2nd Progress Report to Parliament. Committee on Climate Change, June 2010. TheCCC.org. Web. 24 Sept. 2013.

Hulme, Mike. Why We Disagree About Climate Change: Understanding Controversy, Inaction and Opportunity (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009).

Kingsnorth, Paul. ‘Confessions of a Recovering Environmentalist.’ Orion Magazine Jan.-Feb. 2012. OrionMagazine.org. Web. 24 Sept. 2013.

Nickerson, Sheila. ‘Earth on Fire.’ Interdisciplinary Studies in Literature and the Environment 5.1 (1998): 67–87. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/isle/5.1.67

Szerszynski, Bronislaw. ‘The Post-Ecologist Condition: Irony as Symptom and Cure’ in Ingolfur Blüdhorn and Ian Welsh (eds), The Politics of Unsustainability: Eco-Politics in the Post-Ecologist Era. Special issue of Environmental Politics 16.2 (2007): 337–55.

Please feel free to comment on this article.

Climate fiction ('cli-fi') has a huge role to play in engaging people in climate change issues. Here's a link to a FB cli-fi group https://www.facebook.com/#!/groups/320538704765997/