Rob Gallagher

In his essay ‘Strange Gourmet: Taste, Waste, Proust’ Joseph Litvak discusses a tendency among marginalised youths, and especially among queer ones, to seek solace in the idea of ‘some other place, some other world, magically different from the world of family and school’ (76). The ‘other worlds’ Litvak cites — ‘”Broadway,” “Hollywood”… “Greenwich village”’ (76) — belong to a pre-digital pop cultural landscape, but his point is equally applicable to virtual playscapes, from Super Mario Bros.’ mushroom kingdom to World of Warcraft’s Azeroth. As alluring as these worlds may be, one is eventually expected to outgrow them, to admit that there is something juvenile about so longing to escape reality. For Litvak however there is an alternative to simply relinquishing our attachment to these dreamworlds: we can instead develop ‘an endlessly renewable… gift for inversion’ (76), learning to switch between surrendering to our fantasy and acknowledging its ‘objective’ impossibility or thinness. Litvak’s primary example here is the dialectic of captivation and contempt which characterises Marcel’s attitude to the French aristocracy in Proust’s À la recherche du temps perdu. Having long dreamed of entering society Marcel discovers upon attaining his goal that he himself has invested the Faubourg St. Germain with what glamour it appeared to possess. He is not so much troubled by this revelation, however, as he is beguiled by his own capacity to alchemically transmute ‘a gift of shit (in Jacques Lacan’s charming phrase)’ into ‘what Proust calls “celestial nourishment”’ (76).

Powerful dreamworlds: imaginary “other worlds” such as Hollywood, Proust’s À la recherche du temps perdu and Greenwich Village can help us understand digital metaphors used in virtual gameworlds

[Images (from left to right) by Alexis Fam under a CC BY license; by un singe qui parle under a CC BY-NC-SA license; by Ed Yourdon under a CC BY-NC SA license]

The spatial and optical metaphors that underwrite Litvak’s account [1] – flat and full, flipping and (re)framing – are entirely appropriate given Proust’s fascination with anamorphosis, optical illusion and spatial ambiguity. This interest is incarnated in the character Elstir, a painter whose landscapes, ‘bring out certain… laws of perspective’ (483) by presenting apparently impossible landscapes which the viewer must then make sense of. [2] As critics have observed, Elstir’s method might be said to metaphorise Proust’s practice as a novelist, his habit of relating apparently inconsequential incidents that will later assume a profound significance, of introducing characters in terms and circumstances that are, if not strictly speaking deceptive, then hard to reconcile with the impression we will form as we assume other ‘perspectives’.

On occasions Proust seems to hold that there can be no definitive or objective perspective on reality. On other occasions, however, he inclines towards what Descombes dubs an ‘old-fashioned intellectualist psychology’, whereby ‘the intelligence is supposed to correct the [mistaken] impressions of the senses’ and we only need to assume the correct viewing position to see the truth (265). The tension between these two stances is most pronounced when it comes to questions of sexual identity – and particularly the narrator’s paranoia regarding his beloved Albertine’s putative lesbian tendencies. Gripped by jealousy Marcel begins, in the wake of Albertine’s death, to obsessively re-view and reframe the past, investing innocuous incidents with a (for him at least) profound and baleful significance. [3]

The sexual mores of Fin de siècle socialites may not seem to have obvious implications for our understanding of digital metaphor. I want to suggest, however, that Proust’s pointed queerings of novelistic spacetime hint at possible uses of spatial, optical and perspectival metaphor in virtual environments, and illuminate the ways in which games like Polytron’s Fez and Intelligent Systems’ Super Paper Mario are already employing such metaphors. These titles may be worlds apart from Proust in terms of content, but they too demonstrate how warping space can work to expressive ends, manifesting a similar interest in the mechanics of (mis)perception.

Rotating Fez’s world: as the gap between platforms disappears from view it ceases to impede the avatar

[Image derived from a video by Polytron Corporation, used under fair dealings provisions]

Reorienting the camera opens up a third axis of movement in Super Paper Mario

[Image derived from a video posted by NintendoGolinHarris, owned by Nintendo; used under fair dealings provisions]

Both Fez and Super Paper Mario hark back to the two-dimensional ‘platform’ games of the eighties and nineties, the genre that the original Super Mario Bros. essentially invented. In this they are not unusual: many modern games explore older genres and styles. The difference with Fez and Paper Mario is the conceit of switching between 2D and 3D. Progressing through these games’ worlds entails reading space as alternately ‘deep’ and ‘flat’ in order to find paths and solve puzzles: in Fez our avatar can only move in two dimensions, but we are free to rotate the camera in ninety degree increments, aligning forms with the screen’s plane to create pathways; in Super Paper Mario we can periodically switch from a 2D playfield to a ‘deep’ space seen from behind the avatar.

But reframing is more than a play mechanic in these titles; it is also a means of making space signify, of posing questions about nostalgia, fantasy, technology and perception. By having players repeatedly alternate between seeing in two- and three-dimensional terms, these games at once recapitulate the shift that videogames graphics made from flat bitmaps to filled-out polygonal forms (from the original Super Mario Bros. to Super Mario 64) and gesture at the degree of imaginative investment players had to make in ‘fleshing out’ the abstract, two-dimensional representations of early videogames.

From two to three dimensions: 1985’s Super Mario Bros. and 1996’s Super Mario 64

[Images by Nintendo, used under fair dealings provisions]

In the 1990s the progression from two- to three-dimensional gameworlds seemed to many like a natural and irreversible shift, another stage in a journey away from the crude metaphors of yore toward coherent and realistic digital representations, indistinguishable from reality. In Super Mario 64, players accessed new worlds by jumping into paintings – at once a reference to the game’s rounding out of the earlier Mario titles’ flat spaces and a cute reversal of the Gothic tradition of portraits coming alive and breaking their frames. But where that game was concerned with realising the desire to flesh out earlier Mario games’ crudely rendered but evocative representations, Fez and Paper Mario are more about witnessing that desire. Dating from an era when three-dimensional gameworlds have lost their air of millennial promise, when videogames’ players and designers have realised that three-dimensional games are not necessarily any more diverting than their two-dimensional forebears, they nostalgically recall a time when imagination had to supplement shortfalls in processing power. Rather than positing an inevitable onward progression from flat to full, from abstract to realistic, they institute a reversible relation between the second and third dimensions, the past and the present, the perceived and the real, suggesting the extent to which flat playspaces engage us on a metonymic level, whether as prototypes of a fleshed-out future or as documents of a lost childhood.

The kind of optical irony these games require us to cultivate (insofar as we must simultaneously hold two incompossible ‘readings’ of gamespace in our heads at all times) might be said to mirror – or metaphorise – the ambivalence that Litvak detects in Proust, the capacity to relish something while acknowledging that it is also tacky, manipulative, shallow. Mining a semantic slippage between the cultural and gustatory senses of ‘taste’, Litvak notes that those with ‘subtlest (not to say the most jaded) of palates’ often prefer ‘gamier’ dishes, in the sense of meats that are piquantly overripe, rich, pungent (82-3). His metaphor proves felicitously apt in the case of these very ‘gamey’ videogames, which, in an era when many game developers strive for gritty photorealism, remain loyal to notionally ‘primitive’, juvenile, past-their sell-by-date styles. Where games like Spec Ops: The Line strive for pseudo-literary gravitas, the ostensibly ‘gamier’ Fez is arguably more radical in the way that it addresses the appeal of play, the conventions of gaming and the vagaries of subjective perception. Many games’ framing narratives raid Philip K. Dick’s back catalogue, harping on the difficulty of distinguishing appearance from reality, but few have gone as far as Fez in exploring how these themes can shape the actual gameplay experience: here, if it can be made to look like there’s a path, there is one. Fez demonstrates that videogames can tackle questions of epistemology and interpretation, captivation and re-evaluation in an essentially gamic way.

Documents of a lost childhood: Games like Fez and Super Paper Mario institute a reversible relation between the second and third dimensions, the past and the present, engaging us on a metonymic level

[Image by Maria Johnson under a CC BY-NC license]

If Fez and Paper Mario are, like Elstir’s paintings, ‘metaphor[ic]’ (Proust 479), it is less because they involve the substitution of objects for other objects than because they posit analogies between different activities or modes of perception, using processes as figures for other, more complex or diffuse processes. In so doing, they raise a question to which the study of digital media seems destined to constantly return: that of metaphor’s applicability and abuse. Academic videogame criticism has sometimes been guilty of reducing games to figures or exempla – a problem that Espern Aarseth highlighted in the 1990s (165), and which remains sufficiently rife that the journal Game Studies explicitly requests contributors ‘attempt to shed new light on games, rather than simply use games as a metaphor or illustration of some other theory or phenomenon’. Such appeals for rigour are commendable. The fact remains however that digital media often present us with instances where it can be difficult, if not impossible, to determine just where metaphor can be said to stop. As in Proust’s description of Elstir’s technique (which effects a ‘metamorphosis of the objects represented, analogous to what in poetry we call metaphor’ [479]), in which the painter’s practice becomes a kind of metaphor for metaphoricity, the computer confronts us with layers of metaphors nested inside metametaphors.

Here the games I’ve discussed here, which present players not merely with symbolically resonant virtual spaces but with symbolically resonant modes of manipulating and traversing virtual space, present a particularly interesting test case. How are we to understand the relation between the purely cognitive operation involved in, say, ‘reframing’ an optical illusion like the duck-rabbit and that of pushing the button that flips or reorients the landscape in Super Paper Mario? Or between that button press and the realignment of our eyes needed to see an anamorphic image? Is the game recapitulating, allowing us to delegate or offering an image of this process? How valid is it to see the production of (virtual) spatial depth as a figure for temporal transition or imaginative investment (something it would be hard to discuss other than in figurative terms)? Or indeed to compare a mechanic in a Mario game to a vein of Proustian symbolism?

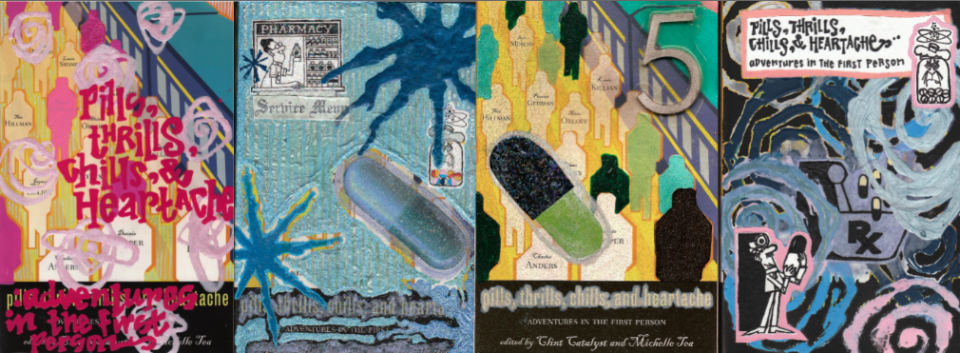

Exploring the queer corner’s of literature: game design needs to pay more attention to interpersonal end emotional experience

[All images by Clint Catalyst under a CC BY license]

In the latter case, hopefully the juxtaposition demonstrates the value of modes of comparative reading that look past subject matter to structures, procedures, techniques. It also, perhaps, helps us to imagine other ends to which games could employ similar forms of spatial metaphor. In both Super Paper Mario and Fez depth play is a means of engaging gaming’s history, but it is possible to imagine titles based around similar reframing mechanics but concerned with other issues. Why not a game that hinges, say, on configuring a frame to promote different ‘readings’ of a scene’s sociosexual dynamics, a la Proust? Or a game about the difficulty of making ‘real life’ coincide with the reductive templates offered by media imagery? Of course, beyond the (not insignificant) barrier of such concepts’ limited commercial potential, the problem with using a viewpoint-switching facility in this way is that while CPUs excel at calculating positions and proximities, geometries and orientations, they tend to struggle with connotation and emotion. As Ian Bogost notes, ‘for better or worse, the capabilities of game engines have been limited to visual and physical experience rather than emotional and interpersonal experience’ (64). He remains optimistic however that we may see game engines that concentrate less on ‘abstract functions for object physics’ and more on ‘abstract functions for human discourse’ in the future, citing Mateas and Stern’s Facade as pioneering in its exploration of the (rather Proustian) thematic terrain of ‘emotional conflict, jealousy and disappointment’ (66, 63). For Noah Wardrip-Fruin, meanwhile, games aiming to address interpersonal behaviour will require not just ‘more complex internal models’ at the level of code but also defter ‘crafting of audience expectations’ on the part of those designing the game’s audiovisual components. Questioning the ‘inside out’ approach to artificial intelligence, Wardrip-Fruin argues that AIs should be understood not merely as autonomous synthetic agents but as performers who must render their behaviour legible to – or at least open to interpretation by – users on the outside looking in. The architects of our digital future, in other words, will continue to need symbols, signposts and metaphors – and they might do worse than exploring the queerer corners of literature’s past.

CITATION: Rob Gallagher, “The Metaphorics of Virtual Depth,” Alluvium, Vol. 2, No. 6 (2013) (“Digital Metaphors” Special issue) : n. pag. Web. 4 December 2013, http://dx.doi.org/10.7766/alluvium.v2.6.03

Dr Rob Gallagher is a postdoctoral research fellow at Concordia University’s Technoculture, Art and Games centre. His PhD thesis, completed at the London Consortium, addressed digital games and the embodied experience of time. His current work considers games as fiction, drawing on platform studies and queer theory to engage questions of affectivity, gender and identity.

Dr Rob Gallagher is a postdoctoral research fellow at Concordia University’s Technoculture, Art and Games centre. His PhD thesis, completed at the London Consortium, addressed digital games and the embodied experience of time. His current work considers games as fiction, drawing on platform studies and queer theory to engage questions of affectivity, gender and identity.

Notes:

[1] Which, incidentally, are strikingly similar to those used in Lacanian theorist Saitō Tamaki’s account of how media-obsessed otaku maintain ‘multiple orientations’ toward media, ‘switch[ing] perspectives flexibly’ to enjoy texts they also acknowledge are embarrassing (25-6)

[2] There are parallels here with Jesse Matz’s (2013) suggestion that the ‘doubleness’ of impressionist canvases (which function both as representations positing 3D spaces and as indexical records of the painter’s brushstrokes) renders them eminently ‘narratable’.

[3] Ana Vadillo’s (2005) work on the ekphrastic poetry of Michael Field suggests there is perhaps more work to be done on sightlines and spatial skewing in late-19th and early-20th century queer literature.

Works Cited:

Aarseth, Espen. Cybertext: Perspectives on Ergodic Literature (Baltimore; London: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1997).

Bogost, Ian. Unit Operations: An Approach to Video Game Criticism. (Cambridge, Mass.; London: MIT, 2006).

Descombes, Vincent. Proust: Philosophy of the Novel. Translated from French by Catherine Chance Macksey (Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press, 1992).

Façade. Michael Mateas and Andrew Stern (2005).

Litvak, Joseph. Strange Gourmet: Taste, Waste, Proust. In: Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, ed. Novel Gazing: Queer Readings in Fiction (Durham, NC; London: Duke University Press, 1997) pp.74-93.

Matz, Jesse. Impressionism as Narrative Painting (After All). Paper given at the International Conference on Narrative, 28 June 2013, Manchester Metropolitan University.

Proust, Marcel. In Search of Lost Time vol. II: Within a Budding Grove. Translated from French by C. K. Scott Moncrieff and Terrence Kilmartin (London: Vintage, 2002).

Tamaki, Saitō. Beautiful Fighting Girl. Translated by J. Keith Vincent and Dawn Lawson (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2011).

Spec Ops: The Line. Yager Development (2012).

Super Mario Bros. Nintendo Creative Department (1985).

Super Mario 64. Nintendo Entertainment Analysis and Development (1996).

Vadillo, Anna Parejo. Women Poets and Urban Aestheticism: Passengers of Modernity (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2005).

Wardrip-Fruin, Noah. Internal Processes and Interface Effects: Three Relationships in Play. In: International HASTAC Conference 2007: Information Year. http://hastac.org/informationyear/ET/BreakoutSessions/9/Wardrip-Fruin [Accessed 15 April 2012].

Please feel free to comment on this article.

One Reply to “The Metaphorics of Virtual Depth”