Zara Dinnen

Metaphor wants to be…

‘[…] metaphors work to change people’s minds. Orators have known this since Demosthenes. […] But there’s precious little evidence that they tell you what people think. […] And in any case, words aren’t meanings. As any really good spy knows, a word is a code that stands for something else. If you take the code at face value then you’ve fallen for the trick.’ (Daniel Soar, “The Bourne Analogy”).

Tao Lin’s recent novel Taipei (2013) is a fictional document of life in our current digital culture. The protagonist, Paul — who is loosely based on the author — is numb from his always turned on digitally mediated life, and throughout the novel increases his recreational drug taking as a kind of compensation: the chemical highs and trips are the experiential counterpoint to the mundanity of what once seemed otherworldly — his online encounters. In the novel online interactions are not distinguished from real life ones, they are all real, and so Paul’s digital malaise is also his embodied depressive mindset. The apotheosis of both these highs and lows is experienced by Paul, and his then girlfriend Erin, on a trip to visit Paul’s parents in Taipei. There the hyper-digital displays of the city — ‘lighted signs […] animated and repeating like GIF files, attached to every building’ (166) — launch some of the more explicit mediations on digital culture in the novel:

Paul asked [Erin] if she could think of a newer word for “computer” than “computer,” which seemed outdated and, in still being used, suspicious in some way, like maybe the word itself was intelligent and had manipulated culture in its favor, perpetuating its usage (167).

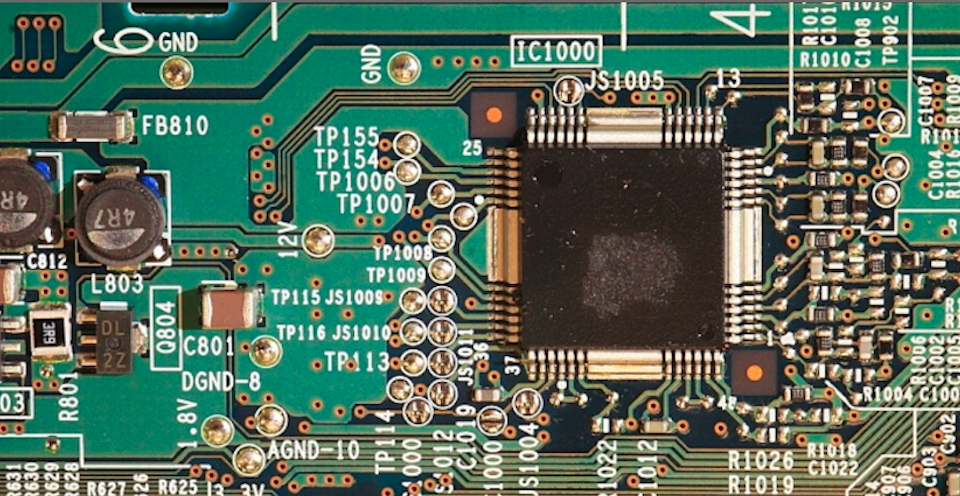

Here Paul intimates a sense that language is elusive, that it is sentient, and that, in the words of Daniel Soar quoted above as an epitaph, it tricks us. It seems to matter that in this extract from Taipei the word ‘computer’ is conflated with a sense of the object ‘computer’. The word, in being ‘intelligent’, has somehow taken on the quality of the thing it denotes — a potentially malevolent agency. The history of computing is one of people and things: computers were first the women who calculated ballistics trajectories during the Second World War, whose actions became the template for modern automated programming. The computer, as an object, is also-always a metaphor of a human-machine relation. The name for the machine asserts a likeness between the automated mechanisms of computing and the physical and mental labour of the first human ‘computers’. Thinking of computing as a substantiated metaphor for a human-machine interaction pervades the way we talk about digital culture. Most particularly in the way we think of computers as sentient — however casually. We often speak of computers as acting independently from our commands, and frequently we think of them ‘wanting’ things, ‘manipulating’ culture, or ourselves.

Pre-electronic binary code: the history of computing offers us metaphors for human-machine interaction which pervade the way we talk about digital culture today

[Image by Erik Wilde under a CC BY-SA license]

Julie E. Cohen, in her 2012 book Configuring the Networked Self, describes the way the misplaced metaphor of human-computer and machine-computer has permeated utopian views of digitally mediated life:

Advocates of information-as-freedom initially envisioned the Internet as a seamless and fundamentally democratic web of information […]. That vision is encapsulated in Stewart Brand’s memorable aphorism “Information wants to be free.” […] Information “wants” to be free in the same sense that objects with mass present in the earth’s gravitational field “want” to fall to the ground. (8)

Cohen’s sharp undercutting of Brand’s aphorism points us toward the way the metaphor of computing is also an anthropomorphisation. The metaphor implicates a human desire in machine action. This linguistic slipperiness filters through discussion of computing at all levels. In particular the field of software studies — concerned with theorising code and programming as praxis and thing — contains at its core a debate on the complexity of considering code in a language which will always metaphorise, or allegorise. Responding to an article of Alexander R. Galloway’s titled “Language Wants to Be Overlooked: On Software and Ideology”, Wendy Hui Kyong Chun argues that Galloway’s stance against a kind of ‘anthropomorphization’ of code studies (his assertion that as an executable language code is ‘against interpretation’) is impossible within a discourse of critical theory. Chun argues, ‘to what extent, however, can source code be understood outside of anthropomorphization? […] (The inevitability of this anthropomorphization is arguably evident in the title of Galloway’s article: “Language Wants to Be Overlooked” [emphasis added].)’ (Chun 305).

In her critique of Galloway’s approach Wendy Chun asserts that it is not possible to extract the metaphor from the material, that they are importantly and intrinsically linked.[1] For Julie E. Cohen the relationship between metaphor and digital culture-as-it-is-lived is a problematic tie that potentially damages legal and constitutional understanding of user rights. Cohen convincingly argues that a term such as ‘cyberspace’, which remains inextricable from its fictional and virtual connotations, does not transition into legal language successfully; in part because the word itself is a metaphor, premised on an imagined reality rather than ‘the situated, embodied beings who inhabit it’ (Cohen 3).

And yet Cohen’s writing itself demonstrates the tenacious substance of metaphoric language, using extended exposition of metaphors as a means to think more materially about the effects of legal and digital protocol and action. In the following extract from Configuring the Networked Self, Cohen is winding down a discussion of the difficulty of forming actual policy out of freedom versus control debates surrounding digital culture. Throughout the discussion Cohen has emphasised the way that both sides of the debate are unable to substantiate their rhetoric with embodied user practice; instead Cohen identifies a language that defers specific policy aims.[2] Cohen’s own use of metaphor in this section — ‘objections to control fuel calls […]’, ‘darknets’ (the latter in inverted commas) — is made to mean something grounded, through a kind of allegorical framework. I am not suggesting that allegory materialises metaphor — allegory functioning in part as itself an extended metaphor — but it does contextualise metaphor.

How tenacious is metaphoric language? The persistence of computational metaphors in understanding digital culture could harm legal and constitutional understandings of user rights

[Image by Christian under a CC BY-NC-ND license]

This is exemplified in Cohen’s description of the ways US policy discussions regarding code, rights and privacy of the subject are bound to a kind of imaginary, and demonstrate great difficulty in becoming concrete:

Policy debates have a circular, self-referential quality. Allegations of lawlessness bolster the perceived need for control, and objections to control fuel calls for increased openness. That is no accident; rigidity and license historically have maintained a curious symbiosis. In the 1920s, Prohibition fueled the rise of Al Capone; today, privately deputized copyright cops and draconian technical protection systems spur the emergence of uncontrolled “darknets.” In science fiction, technocratic, rule-bound civilizations spawn “edge cities” marked by their comparative heterogeneity and near imperviousness to externally imposed authority. These cities are patterned on the favelas and shantytowns that both sap and sustain the world’s emerging megacities. The pattern suggests an implicit acknowledgment that each half of the freedom/control binary contains and requires the other (9-10).

I quote this passage at length in order to get at the way in which the ‘self-referential nature’ of policy discussion is here explained through a conceptual, and specifically literary, framing. Technology is always both imagined and built: this seems obvious, but it justifies reiteration because the material operations of technology are always metaphorically considered just as they are concretely manifest. The perilous circumstance this creates is played on in Cohen’s writing as she critiques constitutional policy that repeatedly cannot get at the embodied subject that uses digital technology; thwarted by the writing and rewriting of debate. In Cohen’s words this real situation is like the science fiction that is always-already seemingly like the real technology. Whether William Gibson’s ‘cyberspace’, a programmer’s speculative coding, or a lawyer’s articulation of copyright, there is no easy way to break apart the relationship between the imaginary and the actual of technoculture.

Perhaps then what is called for is an explosion of the metaphors that pervade contemporary digital culture. To, so to speak, push metaphors until they give way; to generate critical discourse that tests the limits of metaphors, in an effort to see what pretext they may yield for our daily digital interactions. The articles in this issue all engage with exactly this kind of discourse. In Sophie Jones’ “The Electronic Heart”, the history of computing as one of women’s labour is used to reconfigure the metaphor of a computer as an ‘electronic brain’; instead asking whether cultural anxieties about computer-simulated emotion are linked to the naturalization of women’s affective labour. In “An Ontology of Everything on the Face of the Earth”, Daniel Rourke also considers computers as a sentient metaphor: uncovering an uncanny symbiosis between what a computer wants and what a human can effect with computing, through a critical dissection of the biocybernetic leeching of John Carpenter’s 1982 film The Thing. Finally, in “The Metaphorics of Virtual Depth”, Rob Gallagher uses Marcel Proust’s treatment of novelistic spacetime to generate a critical discourse on spatial and perspectival metaphor in virtual game environments. All these articles put into play an academic approach to metaphors of computing that dig up and pull out the stuff in between language and machine. In his introduction to Understanding Digital Humanities David M. Berry has argued for such an approach: [what is needed is a] ‘critical understanding of the literature of the digital, and through that [to] develop a shared culture through a form of Bildung’ (8).

A wheel in the sky: Neil Blomkamp’s futuristic L.A. plays on the territorial paranoia of the U.S. over alien invasion and dystopian metaphors of digitally-mediated environments

[Image used under fair dealings provisions]

I am writing this article a day after seeing Neill Blomkamp’s film Elysium (2013). Reading Cohen’s assertion regarding the cyclical nature of US digital rights policy debates on control and freedom, her allegory with science fiction seems entirely pertinent. Elysium is set in 2154; the earth is overpopulated, under-resourced, and a global elite have escaped to a man-made (and machine-made) world on a spaceship, ‘Elysium’. Manufacturing for Elysium continues on earth where the population, ravaged by illness, dreams of escaping to Elysium to be cured in “Med-Pods”. The movie focuses on the slums of near future L.A. and — perhaps unsurprisingly given Blomkamp’s last film District 9 (2009) — plays on the real territorial paranoia of the U.S. over alien invasion: that the favelas of Central and South America, and the political structures they embody, are always threatening ascension. In Elysium the “edge city” is the whole world, and the technocratic power base is a spaceship garden, circling the earth’s orbit. ‘Elysium’ is a green and white paradise; a techno-civic environment in which humans and nature are equally managed, and manicured. ‘Elysium’, visually, looks a lot like Disney’s Epcot theme park — which brings me back to where I started. In Tao Lin’s Taipei Paul’s disillusionment with technology is in part with its failure to be as he imagined, and his imagination was informed by the Disney-fied future of Epcot. In Taipei:

Paul stared at the lighted signs, some of which were animated and repeated like GIF files, attached to almost every building to face oncoming traffic […] and sleepily thought how technology was no longer the source of wonderment and possibility it had been when, for example, he learned as a child at Epcot Center […] that families of three, with one or two robot dogs and one maid, would live in self-sustaining, underwater, glass spheres by something like 2004 or 2008 (166).

Thinking through the metaphor of Elysium has me thinking toward the fiction of Epcot (via Tao Lin’s book). The metaphor-come-allegories at work here are at remove from my digitally mediated, embodied reality, but they seep through nonetheless. Rather than only look for the concrete reality that drives the metaphor, why not also engage with the messiness of the metaphor; its potential disjunction with technology as it is lived, and its persistent presence regardless.

CITATION: Zara Dinnen, “Digital Metaphors: Editor’s Introduction,” Alluvium, Vol. 2, No. 6 (2013): n. pag. Web. 4 December 2013, http://dx.doi.org/10.7766/alluvium.v2.6.04

Dr Zara Dinnen is Lecturer in Modern and Contemporary Literature at the University of Birmingham. Her research focuses on representations of the digital in contemporary American culture. Zara is Co-Organiser of the Contemporary Fiction Seminar at the Institute of English Studies and Reviews Editor for the AHRC-funded journal Dandelion.

Dr Zara Dinnen is Lecturer in Modern and Contemporary Literature at the University of Birmingham. Her research focuses on representations of the digital in contemporary American culture. Zara is Co-Organiser of the Contemporary Fiction Seminar at the Institute of English Studies and Reviews Editor for the AHRC-funded journal Dandelion.

Notes:

[1] Here I am near N. Katherine Hayles’ formulation of computers as ‘material metaphors’: machines with the potential to ‘transform the metaphoric network structuring the relation of word to world’ (Writing Machines 23). Despite the similar vocabulary I do not intend to invoke Hayles, in part because her formulation relies on the kind of metaphoric rendering of computation that is itself up for discussion in the articles here.

[2] This rhetoric has been exemplified in the UK government’s response to The Guardian’s publication of the Snowden files; they have been unable to find an enforceable balance between agendas to advocate privacy, encourage freedom, and protect both. The catch-all, give no specifics approach is articulated precisely (unwittingly, perhaps?) in a piece by Nick Clegg for The Guardian, “I share the concerns about David Miranda’s detention” <http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2013/aug/23/david-miranda-rights-security>

Works cited:

Berry, David M. “Introduction.” Understanding Digital Humanities. Ed. David M. Berry. Basingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012. 1-20.

Chun, Wendy Hui Kyong. “On “Sourcery,” or Code as Fetish.” Configurations 16.3 (Fall 2008): 299-324. Project Muse. Web. 16 February 2011. http://dx.doi.org/10.1353/con.0.0064

Clegg, Nick. “I share the concerns about David Miranda’s detention.” The Guardian. Guardian Media Group, 23 August 2013. Web. 24 August 2013.

Cohen, Julie E. Configuring the Networked Self: Law, Code and the Play of Everyday Practice. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2012. Author’s Personal Website. Web. 24 August 2013. Pdf.

District 9. Dir. Neill Blomkamp. TriStar Pictures. 2009.

Elysium. Dir. Neill Blomkamp. TriStar Pictures. 2013.

Galloway, Alexander R. “Language Wants To Be Overlooked: On Software and Ideology.” Journal of Visual Culture 5 (2006): 315-331. Sage. Web. 16 February 2011. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1470412906070519.

Hayles, N. Katherine. Writing Machines. Cambridge, MA: MIT P, 2002. Print.

Lin, Tao. Taipei. Edinburgh: Canongate, 2013.

Soar, Daniel. “The Bourne Analogy” (Shortcuts). London Review of Books. 33.13 (2011): 22. London Review of Books. Web. 24 August 2013.

Please feel free to comment on this article.

One Reply to “Digital Metaphors: Editor’s Introduction”