Tony Venezia

Margaret Thatcher once claimed that her greatest legacy was New Labour: the refashioning of the old enemy in her own image. The implications of this are still being felt in the contemporary failure of a collective social imagination to conceive a world radically different from the one we inhabit. To paraphrase Francis Fukuyama, we are living after the End of History, a philosophical gloss on Thatcher’s own There Is No Alternative. But as Jacques Derrida pointed out in his response to Fukuyama, we remain haunted by a sense of a future that failed to materialise. Whilst Derrida’s concept of hauntology and spectral politics has been widely explored in academia, it arguably found a more pleasing prolongation in peripheral elements of avant-garde pop culture; in the music of the Ghost Box record label and of DJ/musician Burial, in the imagetext cut and paste post-rave collages of Laura Oldfield Ford’s fanzine Savage Messiah (2005-2009), and in the para-academic online commentaries of Mark Fisher and Simon Reynolds. This pop culture manifestation brings to light an intriguing spectral inheritance. Following Thatcher’s demise commentators reminisced on the ‘carnival of dissent’ of 1980s pop music that her policies provoked, in contrast to the gentrified pop scene of today. Today such dissent is arguably relegated to the more experimental margins of pop culture where hauntology reveals glimpses of an uncanny legacy: the technological utopianism of an aborted social democracy that Thatcherism derailed. An untimely ghostly legacy whose parameters I want to trace below.

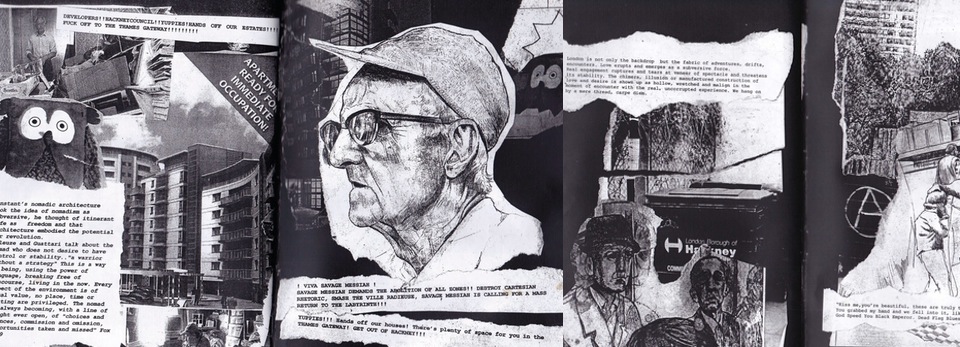

Savage Messiah: Laura Oldfield Ford’s fanzine reveals Thatcher’s uncanny legacy in contemporary experimental pop culture

[Image by Laura Oldfield Ford; used under fair dealings provisions]

Like its fellow traveller, psychogeography, hauntology had continental origins and crossed over to Britain, this time following a trans-Atlantic route.[i] Following this crossing it underwent some revision. In his overview of sonic hauntology, Jamie Sexton suggests that the political aspects of Derrida’s investigation ‘have largely been downplayed in order to focus on the more ontological sense of hauntology: that being itself is haunted, constituted from a number of traces whose presence is felt but often unacknowledged’ (Sexton, 2012: 562). While this is true to a large extent, it is also the case that some commentators specifically enrol hauntology as political critique. The most well known is Mark Fisher, sometime academic, writer, and blogger (as k-punk), and former music journalist Simon Reynolds.[ii]

Reynolds proposed that hauntology ‘suggested solemn laboratory researchers investigating the sonic paranormal’ (Reynolds, 2011: 329). In spite of its Francophone origins and trans-Atlantic trajectory Reynolds views hauntology as a peculiarly British phenomenon, a native counterpart to U.S. hip-hop in its use of similar techniques – sampling, audio loops, crate digging – alongside the referencing of more indigenous cultural traditions. Samples are pillaged from 1970s public information films (a popular source) and library music themes from post-war British horror and science fiction films and television.

Hauntological reference points: electronic musical project The Caretaker takes its name from Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining

[Image by Entertainmentfuse.com; used under fair dealings provisions]

In terms of style, an aural sense of time out of joint is generated by the stitching together of looped samples along with the foregrounding of recording noises that signify decay and deterioration. Combined with the use of reverberation to amplify the sonic eeriness, the resultant sound eerily evokes dead presences. A key early example is The Caretaker’s album, Selected Memories from a Haunted Ballroom (1999). The Caretaker is a project run by electronic musician James Leyland Kirby. The name is borrowed from the role of a key character in Stanley Kubrick’s film The Shining (1980), a key hauntological reference point. In the film Jack Nicholson plays a hotel caretaker in an off season hotel, The Overlook, who struggles against the uncanny malaise hanging over the place and attempts to re-enact the murders of a previous caretaker who went insane and murdered his family. The album attempts to imagine what kind of music would have been heard in The Overlook by taking 1930s popular music, especially Al Bowlly, a popular singer between the wars, and subjecting it to distortion and degradation through reverberation and delay.

Fisher argues that The Shining is a crucial proto-hauntological film, responding to the crisis of postmodernism’s waning of historicity and anticipating the preoccupations of twenty-first century hauntology. The Shining’s looped enactment of crisis (the psychotic caretaker is absorbed into a 1920s photograph of the hotel on a New Year’s Eve – his ghostly predecessor informs earlier in the film him that he has always been the caretaker) is an explicit foregrounding of anachronism: ‘[The Shining] engages with a specific historical crisis – a crisis of historicism itself – that would only intensify in the years since it was released’ (Fisher, 2012: 19).

This impression of uncanny ambience can been found in the output of the record label Ghost Box, established by musicians Jim Jupp and Julian House. This supernatural mood is married to another aspect that connects with Derrida’s proposition of time out of joint: the sense of being haunted by the future. The use of public information samples and the influence of the sound experiments of the BBC Radiophonic Workshop point to a reflexive nostalgia for the unfulfilled technocratic utopianism of the pre-Thatcherite Welfare State, ‘a wistful harking back to the optimistic, forward-looking, benignly bureaucratic Britain of new towns and garden cities, comprehensive schools and polytechnics’ (Reynolds, 2006: 29). These are the ghostly remnants of an interrupted and obliterated by the onslaught of neo-liberal economics after 1979. Fisher contends that this more than anything else defines hauntology, a cultural gridlock brought about by the failure of the future to appear. This means that the future is ‘always experienced as a haunting: as a virtuality that already impinges on the present, conditioning expectations and motivating cultural production’ (Fisher, 2012: 16).

Lost Garden Cities: the sound experiments of the BBC Radiophonic Workshop recall the unfulfilled utopianism of the pre-Thatcherite Welfare State

[Image by Mr Gue under a CC BY-NC-ND license]

The acts on Ghost Box, such as The Focus Group, The Advisory Circle, and Belbury Poly, channel these twin obsessions through disjointed sample and reverb heavy pieces. The sound of The Focus Group (House’s in house project) in particular is characterised by a dislocated audio collage that draws on abruptly edited fragments of folk and jazz, often undercut by their sound processing.

These dissonant sonic collages find a visual corollary in Laura Oldfield Ford’s Savage Messiah. Serialised and self-published from 2005 to 2009, Savage Messiah collages image and text to produce a record of a decaying London landscape. These were subsequently collected into a glossy complete edition and published by Verso press. The name is a reference to the French modernist sculptor Henri Gaudier-Brzeska, famous for developing a primitivist style, while the format employs a punk DIY aesthetic.

Oldfield Ford reads the city through layers of erasure and overwriting that map the transient and ephemeral nature of the urban environment. Ford places herself into narratives that blur between the fictive and non-fictive, her personal story bleeding into those of others and into the history of places. It is a montage method that also owes something to both DJ culture and Walter Benjamin in its cross fading of different spaces and times. Savage Messiah constantly emphasises the relationship between music and place, and how music can reshape places. This is evident in the anachronistic form of Oldfield Ford’s work, which mixes photographs, typeface text, and drawings, scissor cut and glued together and then photocopied, rather than cut and pasted digitally. Her work is populated by marginalised subcultures – punks, squatters, ravers, activists and football hooligans. Her crude collages are a deliberate rebuke to the photoshopped digital images of increasingly privatised public urban spaces.

Fisher suggests that ‘Haunting is about a staining of place with particularly intense moments of time. […] Savage Messiah invites us to see the contours of another world in the gaps and cracks of an occupied London’ (Fisher, 2011: xv). This other world is the dream of collectivism that neoliberal development killed off, the techno-utopianism buried in Ghost Box’s recordings. The city is haunted by the euphoria of warehouse raves of years gone by, the melancholy collages embodying a post-rave comedown.

The soundtrack to this come down can be found in the music of London DJ/musician Burial. Emerging from London’s dubstep scene, Burial’s (pseudonym for William Bevan) self-titled debut album was released in 2006. As well as the now customary foregrounding of crackle and hiss, there is the amorphous sound of booming bass, frantic percussion, and longing vocal samples. The album is a soundtrack to a Ballardian vision of London submerged under a deluge, the rumbling sound of falling rain another ingredient of the soundscape. This is a post-rave music overture for the inevitable comedown, ‘more suited to melancholy private reverie than rave-floor action. This is hauntological dance music for abandoned nightclubs’ (Reynolds, 2011: 393).

The Spirit of ’45: Can we really blame Thatcher for the single-handed destruction of the Welfare State as depicted by Ken Loach in his 2013 documentary?

[Image used under fair dealings provisions]

There is the distinct sense here that rave’s utopian reclamation of public spaces has been usurped by something more sinister. The bastard offspring of Thatcher’s Canary Wharf development can be found in the ever-increasing privatisation and regulation of previously public owned spaces: in Liverpool One, Bristol’s Cabot Circus, and the Olympic Park (Minton, 2012). As Owen Hatherley has pointed out, powers brought in after 1945 to legally bypass slum landlords, such as Compulsory Purchase Orders – are now used ‘to the opposite end’ to hand over swathes of land to private ownership (Hatherley, 2010: xvii).[iii]

The reference to 1945 is unavoidable, as the date for the election of Clement Atlee’s Labour government and the establishment of the Welfare State. The post-war consensus was, for a time and for many, the apotheosis of social democracy.[iv] The moment has recently been the subject of Ken Loach’s cinematic hagiography, The Spirit of ’45 (2013). If anything, however, Loach’s film represents the left’s ongoing inability to come to terms with Thatcher’s legacy. For Loach, the only dates that matter are 1945 and 1979. It is as if Margaret Thatcher appeared from nowhere to dismantle the New Jerusalem. Instead what has happened is the steady erosion of the principle of universalism, a process that the Labour party has been complicit in.

Hauntology reveals the aborted future of the Welfare State as an unfinished project, a path not taken, rather than nostalgia for a time and place. This is also to acknowledge the weaknesses of post-war social democracy. As Fisher has pointed out: ‘One of the futures that haunts those who count themselves progressive, then, is the possibility of a culture that could continue what had begun in post-war social democracy, but that could leave behind the sexism, racism, and homophobia which were so much a feature of the actual post-war period’ (Fisher, 2012: 18).

Clearly, what hauntology (dis)embodies is not a restorative nostalgia. Nor is it reducible to facile retro-futurism; in music and visual forms we are not seeing the straightforward reproduction of old styles, but rather their discomposition which is a reflexive symptom of the collective failure of the social imagination. In this, hauntology in its pop culture aspects functions as a negative dialectic struggling with this legacy of Margaret Thatcher, reminding us of the failure to imagine an alternative and in doing so stressing the necessity of attempting to do so. This is the legacy that we are left with. The question is, is there anything beyond spectral politics?

CITATION: Tony Venezia, “Utopia Loops, Ghost Legacies,” Alluvium, Vol. 2, No. 4 (2013) (“Thatcher’s Legacies” Special Issue): n. pag. Web. 21 July 2013, http://dx.doi.org/10.7766/alluvium.v2.4.05.

Dr Tony Venezia recently completed a PhD on Alan Moore and the historical imagination at Birkbeck, University of London. He is a visiting lecturer teaching English and film at Birkbeck and Middlesex University and has published articles and reviews in a number of academic journals, including Peer English, Radical Philosophy, New Formations, and Visual Culture in Britain. [/author_info][/author]

Dr Tony Venezia recently completed a PhD on Alan Moore and the historical imagination at Birkbeck, University of London. He is a visiting lecturer teaching English and film at Birkbeck and Middlesex University and has published articles and reviews in a number of academic journals, including Peer English, Radical Philosophy, New Formations, and Visual Culture in Britain. [/author_info][/author]

Notes:

[i] Specters of Marx was first presented as a series of lectures on the future of Marxism at the University of California, Riverside in 1993.

[ii] This intermedial aspect of sonic hauntology is explored in more detail by Sexton, 2009. For examples see Fisher’s ‘Hauntology Now’ (2006a) and Reynolds’ ‘Haunted Audio’ (2006), both from their blogs. A more critical example is James Bridle’s ‘Hauntological Futures’ (2011). The website of the record label Ghost Box further emphasises this intermedial aspect.

[iii] Hatherley points out that this state of affairs escalated during the New Labour years, but has its roots in Westminster Council policy of gerrymandering under arch-Thatcherite Shirley Porter in the 1980s. The council deliberately rehoused council tenants, who generally voted Labour, out of the borough in inferior accommodation, then selling of often highly desirable central located council-owned properties to upwardly mobile buyers. See Hatherley, 2010: xvii-xviii.

[iv] For some, this did not go far enough. In B.S. Johnson’s 1973 novel, Christie Malry’s Own Double-Entry, the disaffected title character applies the principles of double-entry book-keeping to his own life and society around him. One of his entries perfectly captures the dissatisfaction felt by many to the idea that the revolution had stalled with Harold Wilson: ‘Socialism not given a chance.’ (Johnson, 1973: 152).

Works Cited:

Bridle, James (2011) ‘Hauntological Futures’, booktwo.org, 20 March, URL [accessed January 2013]: http://booktwo.org/notebook/hauntological-futures/.

Burial (2006). Burial. Hyperdub.

The Caretaker. Selected Memories from the Haunted Ballroom (VvM, 1990).

Derrida, Jacques. Specters of Marx: The State of the Debt, the Work of Mourning, and the New International, trans. Peggy Kamuf (London: Routledge, 1994).

Fisher, Mark. ‘Hauntology Now’, k-punk, 17 January 2006, URL [accessed February 2013]: http://k-punk.abstractdynamics.org/archives/007230.html.

Fisher, Mark. ‘Introduction: Always Yearning for the Time That Just Eluded Us’, in Laura Oldfield Ford, Savage Messiah (London: Verso, 2011), pp. v-xvi.

Fisher, Mark. ‘What is Hauntology?’ Film Quarterly, 66 (1) (2012): 16-24

Ford, Laura Oldfield. Savage Messiah (London: Verso, 2011).

Fukuyama Francis. The End of History and the Last Man (London: Hamish Hamilton, 1989).

Eaton, George. ‘Why Labour should not reverse the Coalition’s child benefit cuts,’ New Statesman, 5 June 2013, URL [accessed June 2013]: http://www.newstatesman.com/politics/2013/06/why-labour-would-not-reverse-coalitions-child-benefit-cuts.

Harris, John. ‘Clampdown – Pop-Cultural Wars in Class and Gender by Rhian Jones – Review’, The Guardian, 16 May 2013, URL [accessed June 2013]: http://www.guardian.co.uk/books/2013/may/16/clampdown-pop-cultural-jones-review.

Hatherley, Owen. A Guide to the New Ruins of Great Britain (London: Verso, 2010).

Jameson, Fredric. Postmodernism, or, the Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1991).

Johnson, B. S. Christie Malry’s Own Double-Entry (London: Penguin, 1973).

Minton, Anna. ‘We are returning to an undemocratic model of land ownership’, The Guardian, 11 June 2012, URL [accessed March 2013]: http://www.guardian.co.uk/commentisfree/2012/jun/11/public-spaces-undemocratic-land-ownership.

Reynolds, Simon. ‘Society of the Spectral’, The Wire, 273 (2006): 26-33

Reynolds, Simon (2006a). ‘Haunted Audio: Dubversion: Deleted Scenes/Re materialised Tangents/Bloopers/Offcuts’, blissblog, 5 December 2006, URL [accessed January 2013]: http://blissout.blogspot.co.uk/2006/12/haunted-audio-dubversion-deleted.html.

Reynolds, Simon (2011). Retromania: Pop Culture’s Addiction to its Own Past (London: Faber and Faber, 2011).

Sexton, Jamie. ‘Weird Britain in Exile: Ghost Box, Hauntology, and Alternative Heritage,’ Popular Music and Society 35 (4) (2012): 561-584, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/03007766.2011.608905

Please feel free to comment on this article.