Adam Stock

When contemporary artists work alongside scientists with “wet hands” in the bioscience laboratory, the results can test both scientific and moral imaginations. New uses of living material raise multiple ethical issues, and a concern for future effects and changes that can be extrapolated from so-called “bioart” practice into a wider social context is at the heart of these ethical conundrums. Bioart, then, may ask us to consider many of the same questions as the dystopian imaginaries of the future in literary texts. Such narratives usually project forwards into the future in order to look backwards critically towards our own present and near future, (known, in structuralist terms, as proleptic-analepsis), and pose the self-reflexive question “how did humanity get here?” Whilst bioart provokes a more straightforward proleptic imaginary (i.e. projecting what the future would look like if we allowed the commercial exploitation of gene/cellular manipulation to continue unabated), it shares with dystopian fiction a critical capacity to highlight how current trends and existing practices could have broader (and graver) implications in the near future. Unlike the stifling postwar uniform totality of George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four, in the radical neo-liberal dystopian future of Margaret Atwood’s novels Oryx and Crake and Year of the Flood (the “Maddaddam series”) the logic of current Western capitalism is extrapolated and all-powerful multinationals tolerate limited dissent when they think it can do no harm to their political or economic interests. Corporations therefore try – and ultimately fail – to contain the critical potential of artistic expression by making art economically dependent upon corporate interests.

How does Margaret Atwood respond to the British dystopias of George Orwell and Aldous Huxley? [Image by John Keogh under a CC-BY-NC license]

The central artistic figure in the Maddaddam Series is Amanda Payne, an illegal 'Tex-Mex' migrant to the north of the country. She creates 'bioart' installations in an on-going project entitled 'The Living Word':

she was dragging the cow bones into a huge pattern so big it could only be seen from above: huge capital letters, spelling out a word. Later she’d cover it in pancake syrup and wait until the insect life was all over it, and then take videos of it from the air, to put into galleries. She liked to watch things move and grow and then disappear (Atwood, 2010: 67-8, emphasis added).

Amanda began this practice early in life, writing her name in syrup and watching ants scurry to eat it, so that 'each letter had an edging of black ants' (Atwood, 2010: 92). Amanda explains: 'You write things, then they eat your writing. So you appear, then you disappear. That way no one can find you' (Atwood, 2010: 92). Writing her name is an act of defiance: if a powerful corporation discovered she was an illegal migrant, she could be disappeared and ground into hamburgers or sold into sexual slavery. From childhood Amanda is drawn to words that write and unwrite themselves, human artifices that nature slowly breaks apart. As a teenager, Amanda Payne lives with a religious survivalist group called 'God’s Gardeners,' who teach that human language separates humankind from animals, and for whom language itself is therefore holy. Their religious taboo on permanent writing is also a political tactic: writing can be deadly evidence in the wrong hands.

Payne later jokes that her video installation series The Living Word is inspired by the God’s Gardeners. Her title refers to John 1:1. Here, Jesus is “the living word”, but Payne’s pun is revealing: it is she who chooses and creates these words, playing with them even in her allusive title as she shapes them into existence and watches them pass into nothingness. Payne draws life forms into her writing in a participatory process, and as such she is a mirror to a more sinister and ethically questionable intervention into the shaping and moulding of life. In Atwood’s future world the fetish for commodification of the human body is normalised, and genetic engineers splice and mix species without scruples. The only real laws are the social Darwinian imperatives of personal survival and corporate profit. That which does not survive (or is not artificially adapted to survive) is by definition without value.

Jesus Christ is the 'Logos' or living Word of God: Atwood's religious sect references genetic engineering and modification [Image by Raquel Baranow under a CC-BY license]

This society is, then, lawless in the sense that Hannah Arendt defined life under a totalitarian dictatorship: the absence of a formally codified law creates the vacuum wherein (here corporate) terror can flourish (1966: 461-8). There is no law, but offences are everywhere. Genetic modification and the plasticity of life is exploited as far as possible and with no ethical scruples: corporations lace vitamin supplements with GM viruses in order to create a market for treatments they have developed concurrently with those viruses. Amanda Payne stitches together plundered dead matter to observe a process of growth and decay. In contrast, the corporate scientists produce 'Frankenstein-foods,' sheep that grow human hair, pigs with two sets of internal organs that can be harvested for human transplants and many horrors besides. These scientists playing God are engaged in acts of real creation, appropriating not simply waste products as Payne does, but the Commons of biological material, which they adjust in ways that fundamentally and irreversibly alter ecosystems.

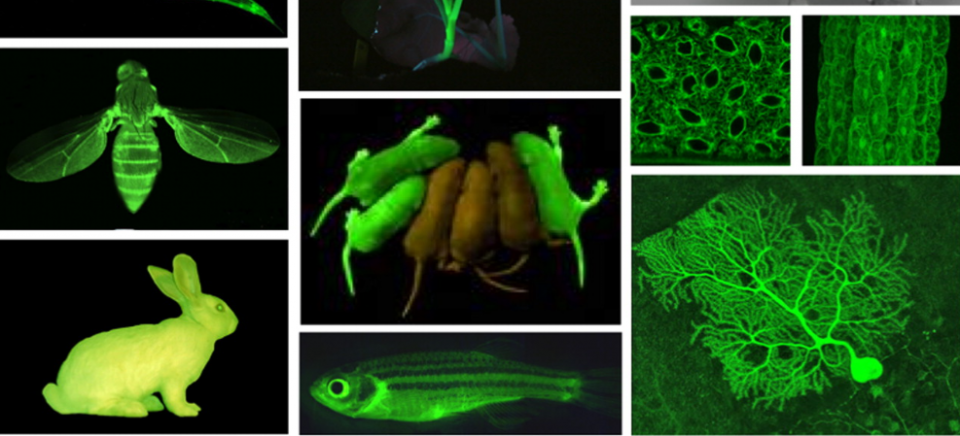

Moreover, while Payne’s work is critical of the corporate hegemony (her last work fittingly involves using dead cow bones to spell 'kaputt') it is a rather gentle intervention in comparison with some contemporary bioart: in 2000 the artist Eduardo Kac created a transgenic 'GFP Bunny' with a French laboratory that glowed green under blue light. Belatedly fearing adverse publicity, the lab then refused to release the rabbit to be shown in a gallery (the piece became a documentation artwork instead). As Jacqueline Stevens notes, biotech companies and scientists are only too happy to assist and to praise such works, which normalise genetic modification even as they raise critical questions (2008: 55), and day-glo rabbits populate the parks of Atwood’s dystopia.

Are GFP images like Eduardo Kac's 'GFP Bunny' [bottom left] normalising genetic modification even as they raise critical questions about dystopian futures? [Source] [Image used under fair dealing provisions]

A more critical intervention can be found in Oron Catts and Ionat Zurr’s Pig Wings Project, the first ever wing-shaped objects grown using pig tissue over scaffolds in the shapes of the wings of bats, birds and ancient reptiles, preserved in a gold coating and exhibited inside jewellery boxes (Miller: 2004, 40). As Catts and Zurr put it:

the narratives we would like to question with our “wet hands” are the narratives of life as a coded program – “biology as information” – and the way it serves the ideology and rhetoric of Western society advancing toward a false perception of total control over life and the technologically mediated victimless utopia (2008: 126).

The artists’ gilded pig wings question what values are really at work in the scientific manipulation of live matter, and seem to play with Horkheimer and Adorno’s observation that 'Enlightenment reverts to mythology' (1997: xvi) by humorously bringing the idea that pigs might fly 'to life.' In arguing that 'Life Is not a Coded Program, and We Are not Our DNA' (2008: 126), the project points to the interaction between different imaginative categories: scientific imagination, pushing back the boundaries of not only what, but how we can know about the world; artistic and aesthetic imagination which seeks new and critical ways of engaging with concepts such as process, identity, play and chance; and lastly moral imagination. The process of making the pig wings provides a narrative framework for engaging with socio-cultural fears, anxieties and risks. Like Amanda Payne’s work, the exhibition of pig wings freezes an organic process, but while Payne’s videos are primarily concerned with the movement of growth and disappearance, Catts and Zurr entrap growth and arrest decay within an archived artefact.

Payne’s work can be both ethically and socially controversial – spelling out critical messages could land her in trouble. Patronising the arts, however, clearly does something for the executives’ liberal consciences. Amanda Payne’s work, documenting flooding and desertification in southern states, does not merely allow the 'execs' to assimilate the cultural trauma of the ecological violence they inflict, and their violence against class, race and gender. Payne herself must pay a heavy price for making the transition from the pleeblands into elite art galleries. She can only secure funding through a 'trade' of sex with a corporate benefactor. As she puts it to her friend Ren, to get funding for the helicopter she from which she films, she 'traded Mr. Big for a whirly' (2010: 68).

Discussing better visions for the future?: Steve Lambert's 'Capitalism Works for Me! True/False' electronic scoreboard [Image by Steve Lambert under a CC-BY license]

In bringing the world beyond the exec compounds to their manicured lawns and total surveillance security, Payne’s art reflects the tactics of today’s artist-activists. As part of the “Anti-Advertising Agency”, for the piece 'Light Criticism' Steve Lambert covered flatscreen advertisements outside New York Subway stations with black foam in which he had cut stencilled slogans, such as “advertising = graffiti”. The play of moving abstract colours showing through the lettering as well as the temporary nature of the work provided a provocative commentary on the appropriation of the Commons of public space by advertisers and graffiti artists alike. More recently, Lambert’s electric sign, styled as a 50s sports scoreboard 'Capitalism Works for Me! True/False,' asks its audience to hit a button below one of two electronic counters marked 'true' and 'false.' The avowed intention is to facilitate the beginnings of critical dialogue. In Lambert’s words, 'the idea that "there is no alternative" to the way our world works takes away our ability to dream. As citizens we need the courage to begin these discussions on order to move on to new and better visions for the future' (Lambert, n. pag.).

Even in Atwood’s dystopia, the executive compounds are not as sealed as the corporations would wish. Corporations kidnap each other’s key workers, while groups like the God’s Gardeners penetrate their compounds, working undercover as health spa managers and grounds keepers. Moreover, a steady trickle of execs, disaffected teenagers and disgruntled spouses leave for the pleeblands, often carrying intelligence information to hand over to opposition groups. In all of these exchanges, there is moral ambiguity and uncertainty. This is particularly the case in the final collapse of civilisation at the hands of a genetically engineered plague hidden inside a sex pill and the creation of a new species of innocent humans (in the Biblical sense). Critical art is validated as a form of creative labour that provides a means to think about and discuss the ethical and aesthetic sides of wider social and cultural concerns in order to begin re-imagining a radically different mode of production and living.

CITATION: Adam Stock, "Making Art in Dystopia," Alluvium, Vol. 1, No. 3 (2012): n. pag. Web. 1 August 2012, http://dx.doi.org/10.7766/alluvium.v1.3.02.

[author] [author_image timthumb=’on’]http://www.alluvium-journal.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/12/Screen-Shot-2012-06-05-at-19.19.41.png[/author_image] [author_info]Dr Adam Stock completed his PhD, Mid-Twentieth Century Dystopian Fiction and Political Thought, in December 2011. He teaches in the English Studies department at Durham University and writes on apocalypse, dystopia, and the relationship between visual arts and literature. [/author_info] [/author]

Works cited:

Adorno, Theodor W., and Max Horkheimer. Dialectic of Enlightenment (London: Verso, 1997).

Arendt, Hannah. The Origins of Totalitarianism (San Diego, California: Harcourt, 1966).

Atwood, Margaret. Oryx and Crake (London: Virago Press, 2009).

Atwood, Margaret. The Year of the Flood (London: Virago Press, 2010).

Catts, Oron and Ionat Zurr. “The Ethics of Experiential Engagement with the Manipulation of Life” in Beatriz da Costa and Kavita Philip (eds.) Tactical Biopolitics: Art, Activism, and Technoscience (Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press, 2010).

Lambert, Steve. “Capitalism Works For Me! True/False”. Artist’s documentation (online archive), 2011: http://www.visitsteve.com (accessed 21 July 2012).

Miller, Arthur I. Art & Science: Merging Art and Science to Create a Revolutionary New Art Movement. Exhibition e-catalogue. GV Art Gallery 7 July – 24 September 2011: http://www.gvart.co.uk (accessed 21 July 2012).

Stevens, Jacqueline. “Biotech Patronage and the Making of Homo DNA” in Beatriz da Costa and Kavita Philip (eds.) Tactical Biopolitics: Art, Activism, and Technoscience (Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press, 2008).

One Reply to “Making Art in Dystopia”